Bridges in Pittsburgh: Towards a Buberian Muslim–Hasidic Dialogue

“All real living is meeting.” — Martin Buber, I and Thou

Today, after the Friday Jummah prayers at the Islamic Center of Pittsburgh, I took a bus from the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh — Pittsburgh’s educational and cultural heart — up to nearby Squirrel Hill, which I have long called Pittsburgh’s “Brooklyn”. Squirrel Hill is a bustling city suburb full of restaurants, book stores, pizza shops and cafes. And it is also the heart of Pittsburgh’s Orthodox Jewish community.

One often sees Orthodox and Hasidic Jews — young and old — walking along the main Murry Avenue corridor. Hasidic boys were gathered along the sidewalks talking, enjoying ice cream and the warm, sunny late September weather having just got out of school. One Hasidic boy in a yarmulka, books in hand and a messenger bag slung under his arm, ran for his life to catch a bus to take him home. As it was late Friday afternoon, there were more Orthodox and Hasidic Jews out than usual as they went out to shop and to prepare for Shabbat — the holiest day of the week for Jews, and which begins at sundown on Friday night. At this point, all working ceases, and Hasidic Jews join together for a special Shabbat meal, and for a joyous time together praising God along with family and community.

In my time in Pittsburgh, I have always loved spending time in Squirrel Hill. And I have always admired the Orthodox and Hasidic communities for their sincere faith, their close communities, and their dedication to God. Working at one of the most primer florists in Pittsburgh in the late 2000s, I would often travel to the homes of well-to-do Jewish families in the Squirrel Hill and Fox Chapel areas around this time of year to help them set up their Sukkot booths. The connection between Sukkot and our American-Puritan roots of Thanksgiving was not lost on me.

More than once in my time in Squirrel Hill, little Hasidic boys have run up to me — flyers in hand — to invite me to their Sukkot parties. “I would love to come,” I would reply, “but you see, I’m not Jewish.”

“That’s funny… you look Jewish!” was the usual reply.

Do I? I don’t know. Walking through Squirrel Hill as a Russian Orthodox priest-monk, I was often mistaken for a Rabbi. “Shalom!” people would exclaim to me. Rather than explaining everything, I would just reply back with a warm “Shalom!”

But today, walking in Squirrel Hill post-Jummah prayers, I crossed the street with a Hassidic Rabbi. His grocery bags in hand. “You can cross, sweetie,” the cross guard said to me. I no longer look like a Rabbi. So I am just “sweetie” now. But to the *actual* Rabbi next to me, the cross guard replied: “Hello Rabbi! Beautiful day, isn’t it? I’ll see you on Thursday!” And they continued to chat.

As often happens to me, I wanted to stop and talk to the Rabbi. Not because I want to convert — or that I want to convert him, necessarily. But rather out of a real sense of Buberian “I/Thou” connection. I wanted to get to know him. In the deepest sense. And I wanted him to know me.

This has happened before — and many times before. I often go through walks through Oakland on Friday nights, after prayers and stopping for something to eat. In my Friday walks, I often happen past the Chabad center in South Oakland. Every Friday, I see through the windows the Hasidic Rabbis sitting and talking with Orthodox Jewish college students — often sharing a meal and a glass of kosher wine.

Perhaps part of it is my feeling of loss as a former priest sharing these sorts of moments — a sort of religious fellowship. But it is also my Buberian instinct that wants to ‘join in’ and to truly ‘know’ these people — people who, in my sense, are not strangers to the faith and to God — even despite the current tensions surrounding Israel and Gaza.

Who was Martin Buber?

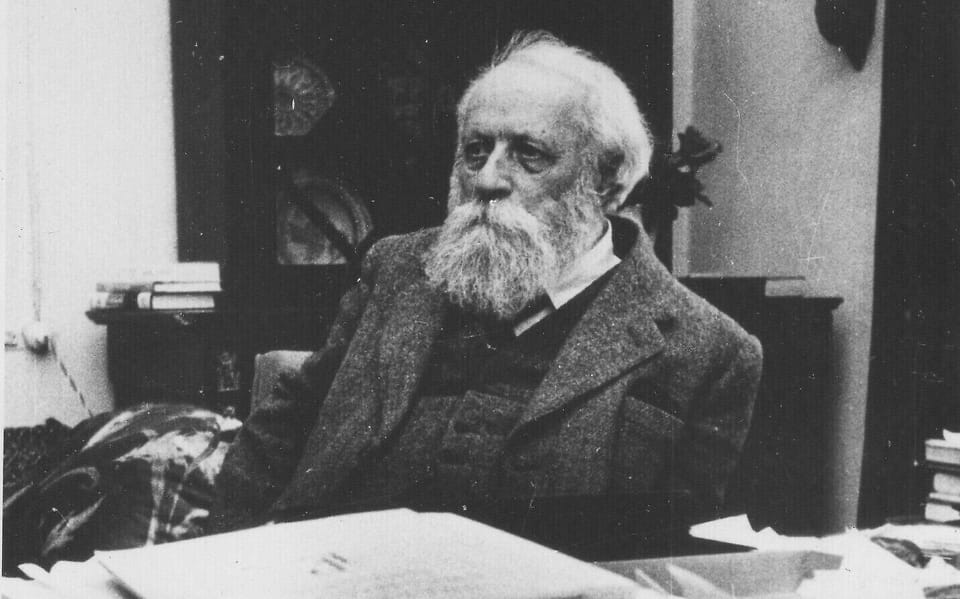

Martin Buber (1878–1965) was a Jewish philosopher, theologian, and interpreter of Hasidic tales whose life’s work revolved around the mystery of encounter. His most influential book, I and Thou (1923), explores the way human beings relate both to one another and to God. It is a book that has greatly influenced my approach to both God and the “other” in recent years.

For Buber, there are two primary modes of relationship: the I–It and the I–Thou. In the I–It relation, we treat others — people, things, even God — as objects, useful or interesting but ultimately external to ourselves. This is the relationship of fundamentalists, of ideologues, of politicians — both of God and of others, in my estimation.

In the I–Thou relation, however, we encounter the ‘other’ in their full presence, without reducing them to a category. In such moments of genuine meeting, we stand before the Eternal. The connection is directly personal. In this sense, God or the ‘other’ is not met as an ends to a means, but rather in the sense of a meeting with the Divine itself — either in the infinite God or in the unique image of the Divine within the individual.

This vision was not an abstract philosophy for Buber. It was deeply spiritual, flowing from his faith and from the Hasidic stories he cherished. In the songs and legends of the Hasidic masters, Buber found examples of people who met one another and God with immediacy and joy. He once wrote:

“In every Thou we address the Eternal Thou.”

For Buber, this meant that every authentic encounter — whether with a friend, a stranger, or the natural world — is also an encounter with God. To speak truthfully, to listen deeply, to meet the other without defenses: all of these were forms of worship.

It is this spirituality of presence, of “real living as meeting,” that makes Buber such a compelling guide for interfaith dialogue today. His work points us toward a way of being with others that is not about argument or persuasion or politics, but about mutual recognition in the light of God.

Towards a Muslim/Orthodox Jewish dialogue?

My hidden secret is that I long for a real, “Buberian” Muslim/Orthodox dialogue. And I don’t think this is something out of the question.

Over the past year, I had been listening to talks by Orthodox Rabbi Tovia Singer. For a while, Rabbi Tovia ran the largest synagogue within the largest Muslim-populated country in the world: Indonesia. While Rabbi Tovia is fully committed to his faith as an Orthodox Jewish Rabbi, he also opened his synagogue to fellowship and talks with Muslims — even going so far to opening a space within his synagogue in which Muslims could pray.

Rabbi Tovia was even an early guest at Blogging Theology.

When I think about dialogue with my Orthodox and Hasidic neighbors, I cannot help but see the parallels between their Hasidic spirituality and the Sufi path within Islam. Both are rooted in the heart rather than the head, in joy rather than aridity, in immediacy rather than abstraction.

Hasidic stories speak of devekut — the cleaving of the soul to God — through prayer, song, and fellowship. The Sufi speaks of dhikr, the remembrance of God’s names until the heart itself becomes remembrance. Both traditions affirm that God is not distant, but encountered here and now in the song, in the story, in the shared meal, in devotion and in prayer.

Rumi, the great Persian Sufi poet, once wrote:

“The wound is the place where the Light enters you.”

And Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk said:

“There is nothing so whole as a broken heart.”

The resonance is unmistakable. Each tradition sanctifies the brokenness of the human condition as the very place of divine encounter.

And are we arguably not ‘broken’ now more than ever before?

The Threshold of Pittsburgh

It may seem strange to imagine such a dialogue not in Jerusalem or Istanbul, but right here in Pittsburgh. And yet, perhaps precisely here, in this city of bridges and neighborhoods, the possibility is more real.

Squirrel Hill carries the beautiful and time-honored rhythms of Jewish life. Oakland pulses with the prayers of Muslims and the learning of students — of all religions and from all over the world. To walk between them is to walk what Buber called the “narrow ridge,” the place where one faith does not dissolve into the other, but where they can turn toward one another in recognition.

Here, far from the centers of conflict and of power, one could imagine small, faithful experiments: a shared evening of storytelling, a circle of song, a meal prepared with reverence — true moments of encounter.

These are not grand interfaith summits filled with cameras and microphones and prepared statements, but ordinary acts of encounter — the kind Buber would say are truest.

What might this “encounter” look like? I am not sure at the moment. But it is, perhaps, something to be fleshed out in the future, Lord willing.

But what we have in common is our true love for the One God — the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob — and the reality of tawhid.

Addendum: On Zionism and the Question of Justice

No honest attempt at Jewish–Muslim dialogue can entirely avoid the shadow that hangs over us: the question of Zionism, and the ongoing struggle in Israel and Palestine. It is the great obstacle to trust, and the wound that bleeds into nearly every conversation.

Martin Buber himself, though a Zionist, was deeply critical of nationalism when it turned into domination. He believed Jews must learn to live with Arabs, not above them. He envisioned a homeland shared in justice, a dream that was never realized but which still speaks prophetically today.

For Muslims, the Qur’an offers a clear warning:

“O believers! Stand firm for Allah and bear true testimony. Do not let the hatred of a people lead you to injustice. Be just! That is closer to righteousness..” (Qur’an 5:8)

Buber’s vision and the Sufi spirit converge here: that dialogue is not sentiment, but necessity. Without it, we remain locked in the world of I–It, reducing one another to objects, enemies, or obstacles. With it, we at least open the possibility of an I–Thou — of recognizing in the other the image of God.

True dialogue also requires moving beyond the ‘false love’ sometimes offered by certain Christian Zionists, who mistake support for Israel with a theology of domination and war. Such a love is not rooted in justice or genuine friendship, but in a misuse of Scripture that instrumentalizes Jews for an imagined apocalypse. Buber’s vision — and the Sufi call to justice — call us to something deeper: a love that seeks peace and the flourishing of the other.

After all, many Orthodox and Hasidic Jews have been against the secular ideology of Zionism. I feel that this is something that we can work around in our mutual love for God and each other.

Closing Reflection

The Qur’an says: “We made you into nations and tribes so that you may come to know one another.” (Qur’an 49:13)

The Talmud teaches: “Whoever saves a single life, it is as if he saved an entire world.” (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5)

Perhaps here in Pittsburgh — this city of bridges — Muslims and Orthodox/Hasidic Jews might yet come to know one another. Not in argument, but in true dialogue. Not in slogans, but in shared understanding. In stories, encounters, and a real sense of adoring the One.

And in that meeting, however small, we may rediscover what Buber taught: that all real living is meeting.

Is this a pipe-dream? Naivete? I hope not.

As Dostoyevsky — an Orthodox Christian — once penned: “The world will be saved by beauty.”

What is more beautiful than a people coming together in the love of God and the love of each other?

UPDATE: In response to this article, somebody sent me this excellent video about the life of Rabbi Menachem Froman ( מנחם פרומן; June 1, 1945–March 4, 2013) who was an Israeli Orthodox rabbi, and a peacemaker and negotiator with close ties to Palestinian religious leaders. He was well known for promoting and leading interfaith dialogue between Jews, Christians and Muslims, focusing on using religion as a tool and source for recognizing the humanity and dignity of all people.

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!