Carl Schmitt, Clausewitz, and the Violence Beneath Democracy

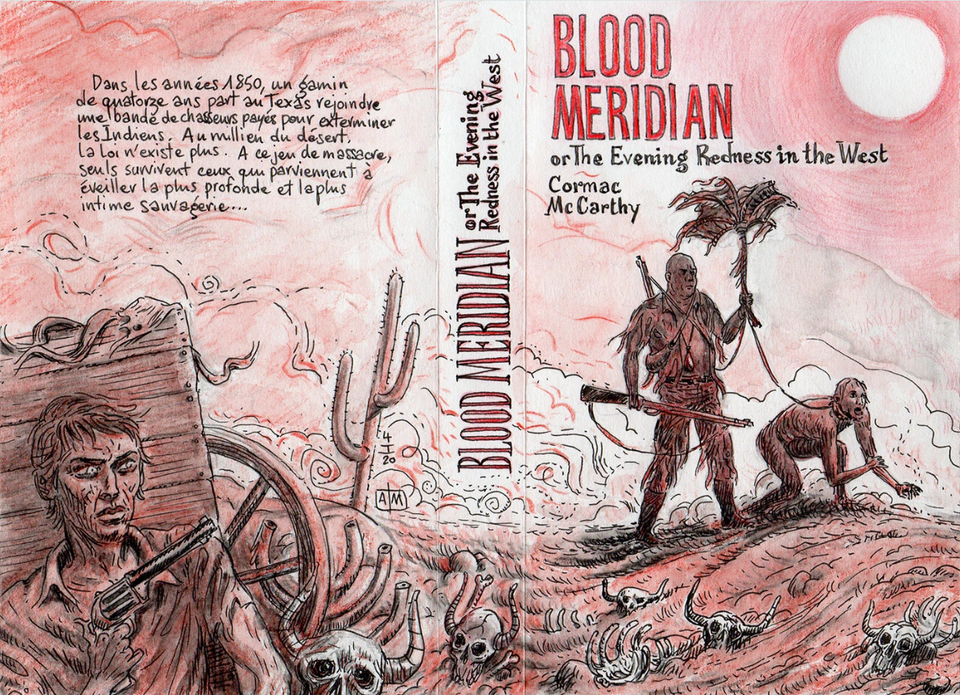

“It makes no difference what men think of war… War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him.”

— Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

My article last night on the Charlie Kirk shooting and the loss of our humanity was a sort of spur of the moment reaction to what had happened, coupled with my own political views. It was charged with some emotion after an unhappy confrontation with a family member and was written all in one go.

Now, after having reflected on what I have written over the past 24 hours, I started to ponder on some of my own reflections on political violence within the United States and within liberal democracies. Though I overall deplored the acts of violence in my piece, I also noted the basis of violence in our American political system in my quoting from the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, I noted some instances of recent violence which seemed to have some popular “approval” of the masses. Once of these examples is that of Luigi Mangione and the “Robin Hood” effect.

In reflection on my own response, I was reminded of what the political philosopher Carl Schmitt once said about liberal democracies. He said, in effect, that liberal democracies were a sort of civilized veneer over the violence that laid just beneath all of political life. It was a veneer that kept this violence in check, which lay just beneath the surface.

The recent shooting of Charlie Kirk forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: what is the place of violence in a “democratic” society? Politicians and commentators — like myself — frame this as an aberration, an act of madness. But thinkers like Carl Schmitt and Carl von Clausewitz remind us that violence is not an exception to politics — it is at its very core.

Clausewitz: War as Politics

Clausewitz’s famous maxim in On War still rings like a warning: “War is merely the continuation of policy by other means.” For him, violence does not mark the end of politics but its most extreme form. When persuasion, bargaining, and procedure fail, politics does not vanish — it escalates into force. War, he argued, is “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.”

Applied to democratic societies, this suggests that when polarization hardens and compromise collapses, violence emerges not as a breakdown of politics but as its extension.

The suggestion that democracy only works when our differences are merely slight. But once these differences widen, there is a point of no return.

The American Revolution was one such instance. And the American Civil War was another. The American South, after all, was not wantonly committing violence in its failed succession from the Union. Rather, it appealed to the very principles laid out in our Declaration of Independence and Constitution, as well as the legacy of the American Revolution itself. A clear example of Clausewitz's “politics by other means”.

Schmitt: The Friend–Enemy Distinction

Carl Schmitt sharpened this point further in The Concept of the Political (1932): “The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.” For him, politics is not primarily about policy, economics, or morality. It’s not even about the “common good”. It is about identity, belonging, and the willingness to confront — and if necessary, destroy — the “other.”

Schmitt argued that democracy itself presupposes exclusion. In The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923), he bluntly stated: “Democracy requires, therefore, first homogeneity and second — if the need arises — elimination or eradication of heterogeneity.” A “people” is defined not just by who it includes but by who it excludes.

The shooting of Kirk — no matter one’s stance on his politics — reveals how the enemy is no longer foreign but domestic. For Schmitt, this is inevitable once political divisions harden into existential ones.

We saw this, once again, in the turbulent 1960s with the assassinations of MLK Jr., JFK, Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy, and the failed attempt on Governor George Wallace — among others.

Liberal Illusions and Absolute Violence

Where Clausewitz describes, Schmitt warns. Liberalism, Schmitt insisted, seeks to erase the friend–enemy distinction by appealing to “humanity” or universal values. But this does not dissolve violence — it radicalizes it. “Whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat,” he wrote. If your opponent is not merely a rival but an enemy of humanity itself, then violence against them becomes unlimited.

We see echoes of this in the moralized rhetoric of American politics: opponents are cast as “traitors,” “fascists,” “communists”, “Islamic radicals” or “enemies of democracy.” Such language risks moving politics from Clausewitz’s “policy by other means” toward Schmitt’s nightmare — violence without limit, because the enemy has been dehumanized.

A Disturbing Mirror

Clausewitz shows us that violence is never outside politics, and Schmitt forces us to admit that democracy is no exception. The Kirk shooting is not a random crack in the system — it is a mirror held up to the way democratic societies draw their lines of inclusion and exclusion.

And, as I argued in my previous article, this is not a flaw in the system under which we live, but the system working just as it was designed.

When the thin veneer of polite society begins to wear thin, then this primordial tribal violence begins to bubble up to the surface.

To American liberals, the boogeymen of rising fascism, Nazis and KKK are a call — justified or not — to stop it “by any means necessary”. The media have fueled these flames for years, and it’s spilling over in shootings in churches, religious schools, an attempt on President Trump — and quite possibly the Kirk shooting. To Republicans and American conservatives, the perceived rise of radicalism of the “Left” and of “Communism”, creeping Shariah Law, etc. has led to shootings at a synagogue in Pittsburgh (just two blooks down the street from where I once lived), hatred of immigrants, shootings in Mosques, Sikh temples (again, in Pittsburgh), and other such politically motivated acts of violence.

So, in light of my own article which I penned last night, I began to ask myself: are these acts of violence really an aberration in our political system? Was there ever really a point in American political life in which civility and the “common good” itself was not the norm, but rather itself the aberration?

Perhaps the question we face is not whether violence has a “place” in democracy — as it seems that it is there, just under the polite and moral surface. The real question is this: how far we are willing to let it go once we have declared our enemies?

I just watched this message and plea from Bernie Sanders — a man that could have been our president if it were not for some political violence within the DNC:

My question the, is this: Is Bernie Sanders correct? Is this really the basis of “freedom and democracy”? Or are we fooling ourselves about the nature of our political system — and of our very human nature?

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!