Convert Types and the Experience of Faith

In April of last year, I wrote a short piece on ‘the convert mindset in the West’. In this piece, I made some observations about the phenomenon and psychology of conversion, and regarding converts to Islam in ‘the West’, I made reference to Abdul Hakim Murad by stating:

An embrace of Islam is not a rejection of all that has nourished you in your formative spiritual life as a Christian in the West, but rather a blossoming into a new space into which all of these things just seem to make more sense.

Nearly a year and a half after writing this — and after a year studying at an Islamic school — my thoughts about the nature of conversion have continued and have deepened. Now, in the latter half of my life, I have first-hand experience not only as a priest and pastor watching the ebb and flow of converts within apostolic Christianity, and not only by witnessing the phenomenon of conversion within Islam — but by analyzing the turns and metamorphosis of my own conversion and its effects on other people. How do people respond? What are their assumptions regarding my conversion? What is expected of me? And so on.

Recently, a friend of mind and fellow-convert to Islam, Jared Morningstar, posted a commentary on Facebook on what he sees as the three different types on converts. I wish to quote him in full. He says:

It seems that there are a few different types of converts to religious traditions, which may be observed across the boundaries of different faiths.

The first kind of convert tends to be very focused on religion as identity. Their new faith represents a conversion away from their old life, which they view with distain for one reason or another. Their identification with a particular religious tradition allows them to feel as if they’ve stepped away from past darkness and into a new light. It allows them to feel special — a lucky member of some kind of elite whose community possesses the Truth. As a result, such a person’s faith is often colored by a strong form of exclusivism which sees other traditions and spiritual communities as flawed, off course, or in the most extreme cases, even demonic or outright evil. Additionally, such converts also typically attempt to embody what they perceive as the most stringent form of orthodox belief and practice within their tradition. Because their relationship with their new faith is deeply tied to identity and a sense of possessing the truth or otherwise being in some exclusive relationship with higher realities, their thinking often tends to be very black and white, rigid, and fixated on details. Underneath the extreme zeal of such converts, there is often a great anxiety, as their stringent exclusivism means that if they don’t have the details exactly right, they might unknowingly still be in the dark — not in fact in a privileged relationship with Truth and outside of the pale of the salvation only granted to the chosen community. This intensity of zeal, coupled with the unwillingness to face this core anxiety makes this type of conversion very unstable and reactive. One will often see these types of converts burn out in their faith, leading either to a particularly depressed sort of unbelief or to a succession of conversion to different religions or sects, each time thinking they’ve finally converted to the way of the Truth, but not realizing that even as they’ve changed religious affiliation, the form of their faith as a neurotic exclusivism has remained unchanged, and it is this rather than the religious affiliation which really requires conversion.

The second type of convert is on the other end of the spectrum from the first. This person does not think of religion primarily through the matrix of identity but rather enters deeply into a tradition as a vehicle for more deeply engaging with spirituality, ethics, and beauty — things with which they already had a relationship with prior to conversion, whether they were coming from a different tradition of a lack of religious affiliation. This type of convert does not typically renounce their past as some dark era of total depravity and lack of insight, but they do of course see their conversion as a huge positive, as this shift allowed them to realize their potential in ways previously inaccessible. Rather than an exclusivist perspective, such a convert often has a much more universalist understanding of religion and sees the existence of other spiritual paths as something intentional and beautiful in the world since their attachment to their own faith is about living spirituality more deeply in the world for the sake of beauty and goodness rather than grasping for some exclusive connection with truth or salvation. Many of these converts also end up becoming important figures, both within their own tradition and often to a broader population, as part of what drew them to convert is being able to clearly see the potential for richness and beauty in the tradition they entered into, and as such they are uniquely poised to communicate this perspective.

There is a third type of convert which is probably more common than either of the above mentioned types, but which is often less noteworthy. This is the convert who has taken up a new religious affiliation through particular social contexts, whether it be through a group of friends who belong to this religion or through a spouse of another faith. Whereas both of the above types of converts are typically very engaged with the intellectual aspects of the faith they’ve embraced, this convert is engaging with their new religion primarily as a form of life and a cultural phenomenon. Similar to the first kind of convert, this person likely considers religion significantly through the lens of identity, but unlike the zealous exclusivist, they are thinking of this primarily in terms of belonging to a community they are attached to, rather than more abstractly in terms of a unique relationship with exclusive truth. Like the second type of convert, they are likely to be more open-minded, as they are not strongly rejecting their past life but rather have a capacity to engage with a new community and see the value in this form of life. This type of convert is typically most similar to their cradle co-religionists, as they take a more intuitive approach to their faith rather than the more cerebral approach of both the previous types of converts. Rather than either fixating on the legalistic or dogmatic details of their religion like the first convert, or looking for the universal spiritual truths in the religion like the second convert, this type of person simply works to fit in with the community and typically ends up as a very moderate adherent to the faith.

Of course, all of these types blend in to one another and it may be difficult to place a particular convert squarely into just one of these categories, but nonetheless it does seem that one finds clusters around each of the archetypes.

Under my comments and reaction to this post on Facebook, a traditional Catholic friend asked me if I see myself as the second type of convert. I think while at one point I was squarely in the first category (as many young men are, I believe, when embracing a new faith), I can honestly say that I do see myself in the second category now — but with some qualifications. I of course don’t deny the transcendent element of faith, nor do I deny that there is an objective Truth and Reality. I am not a universalist. And I don’t have grand aspirations to being an ‘important figure’ in any sense.

However, my entry into Islam was very much through René Guénon and a sort of perennialism which I saw built into Islam, and not something outside of it. Even withing Islamic circles, this fondness of Guénon can be a bit controversial, but it’s something that I’ve not hidden in my writing and conversation. It’s something that has always colored my thought — even leading to my early conversion to Orthodox Christianity. It was Guenon, after all, that led the way for me in the beginning into traditional Christianity.

I will explain.

Being raised nominally Protestant, and after a period of agnostic ‘searching’ in my teens and into my twenties in college, I discovered René Guénon. It was 2003, which was the same year I discovered Rumi and Sufi Islam. Coming from a recent background in studying much philosophy and ‘Eastern’ religions — Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, Taoism, etc. — I came across both Orthodox Christianity and Guénon at exactly the same time. It was Guénon who stressed two things: 1) the importance of being part of a living tradition, and 2) the importance of being part of one tradition. The analogy I remember at the time was of digging a well to find water. If you dig multiple places, you will just have many shallow holes. Yet if you continue to dig in one place, you will eventually reach deep enough to find water.

Finding the leap into Islam too insurmountable in 2003, I entered Orthodox Christianity with Guénon’s injunction to seek out Tradition in mind. Dig into the deep Tradition of Orthodox Christianity as far as possible. This led me to discover people like Fr. Seraphim Rose (whom I still admire), and this led me to the monastery and into monastic life, in which I spent most of my adult life. And as a young man, this approach to ‘tradition’ led me increasingly into the first category of the above ‘types’ converts. Christianity — both Catholic and Orthodox — has a tradition. A deep tradition. A mystical tradition. A theological tradition. A liturgical tradition. An apostolic tradition. And thus it made sense to me that it should be followed. We should learn the tradition. We should know the tradition. We should live the tradition. Any attempts to subvert or dismantle the tradition should be resisted. For it is a tradition with its own internal logic. Start pulling at the strings and, like a sweater, it will start to unravel.

I had mentioned my admiration for Fr. Seraphim Rose, who is a tremendously important and influential figure in American Orthodox Christianity. Fr. Seraphim Rose was himself a convert to Russian Orthodoxy from a rather weak American Protestantism, and in his early years he was influenced by Guénon a great deal. Though he would more or less disown Guénon in his later years, he was always influenced by him to one degree or another. And it was Fr. Seraphim Rose who said that the main difference in our time was not so much between one culture or another, but rather between traditional cultures (who all share a sense of the transcendence and of faith) and modernity. It is a loss of the traditional ‘mindset’. All traditional cultures stress order, faith, transcendence, culture, family, beauty, etc., yet all traditional cultures in all places, said Fr. Seraphim Rose, are being flattened by the ever-expanding spread of modernism and modernity. It is this corrupting ‘modernity’ — in the form on nihilism, consumerism, commercialism, loss of faith, etc. — which must be resisted and ‘tradition’ preserved.

It is with this mindset that I set out to defend ‘tradition’ — the tradition of the Church. Traditional Liturgy. And so on. It was this defense which was often, from the outside, seen as ‘reactionary’ or ‘backward’, depending on one’s point of view. It was a type of view of ‘tradition’ that is often found in the ‘first type’ of converts above. “Zealous” to preserve the ‘identity’ or the ‘in-group’. But I think that those who truly knew me understood that I was no mere ‘backward reactionary’ (which I have been called before — and much worse!) Rather, from the very beginning, my mindset has (for better or for worse) been very ‘Guenonian’. (Again, the judgement as to whether this is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ depends on whom you ask.) But it is a view of ‘tradition’ which is very close to what Fr. Seraphim Rose describes above. The loss of a particular view of the world and its replacement with a flat, grey ‘modernity’.

I’ve said multiple times in multiple places that my embrace of Islam was not really a ‘rejection’ of Christianity. Instead, I stand by what I wrote in April of last year, making reference to Abdul Hakim Murad. It is, rather, “a blossoming into a new space”. It’s the place where I am now, with all of the joys, struggles, and ambiguities that this entails.

I regret that there were some who, early on in my ‘conversion’ to Islam, took it upon themselves to speak on my behalf or posing as me, saying things like: “Mashallah! I have been saved my the fires of hell and renounced my priesthood and entered on the Right Path of Islam!” I would never say something like that. I never did, and I never will. Would I not have made the decision that I did if I did not think it was the truth? Of course. But when something becomes such a deep part of yourself, it cannot be discarded so flippantly and carelessly. Not to mention how insensitive it would be to say such things to my friends and family who are Christian.

I wrote last year of conversion and ‘identity crisis’, and I said that “I feel there is often more of pathology than piety in much of American religious life”. I feel the same way now. And often this ‘pathology’ is tied up with the ‘first’ sort of religious convert, as listed above. Is our faith about seeking God? Is it about loving our neighbor? Feeding the hungry and helping the widow? Is it about seeking the inner transformation necessary which can only come through drawing closer to God? Or is it about something else?

There are a myriad many things — little idols — that can come between us and God — be it identity, politics, hatred, fear, ideologies, insecurities, etc. All of these things are stand-ins for one word: Ego.

There is a story about a young man who went to Mt. Athos and he wished to talk to a monastic elder about the secrets of prayer and of the spiritual life. And when he met the elder at the top of the mountain, he was excited to finally have the deep secrets of the faith revealed to him. And then, looking him square in the eye, the elder simply said to the young man: “Kid, just don’t be an asshole and you are in the top ten percent already.”

(This is a true story.)

In the middle age of my own life, this is where I am right now, I feel. Is there ‘objective truth’? Absolutely. Will we ever agree on everything? No. Wherever there is more than one person, there will be division. This is simply human nature. (And as I said before, sometimes we are even divided within ourselves!)

God, however, is One. He is the All-Merciful, All-Compassionate. There is nothing in Him that is lacking.

The more we align our will with the will of God, the more truly human and alive we become. We have had Prophets and Revelation down through the ages to continue to call us back to this Path.

But in the meantime… have patience. Have patience with yourself, and have patience with others. We’re all a little messed up. And especially these days, it seems like things are getting more insane by the minute.

I see some people longing for the Crusades to return to defend Christian Europe. Or a new Jihad to return Islam to the glory days of the Caliphate. Or the call by Zionist Christians for the building of the Temple to usher in the return of Christ. Or Hindu nationalists to revive the Hindu nation of India against all other identities. There are wars and rumours of wars, and chaos bubbling up everywhere.

But the true Crusade is within our own lives. The battlefield of Jihad is our own hearts. Have we made room in our hearts for the Lord? Or is the temple of our heart cluttered with idols? Barren and neglected?

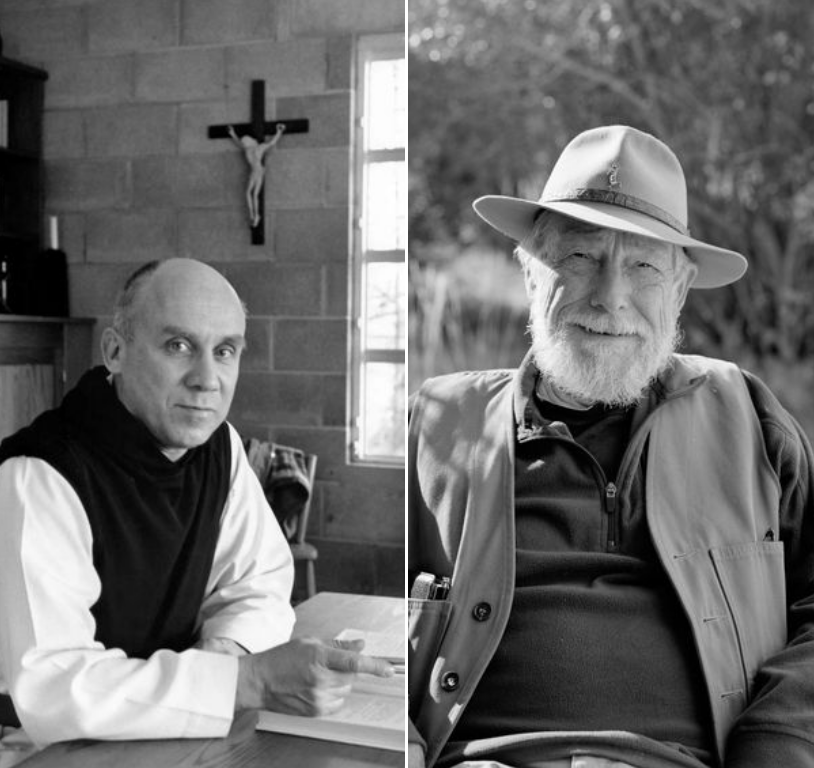

There is so much that can be said here. It’s fair, for example, to point out the more problematic aspects of Merton and Gary Snyder, who are used as examples of the ‘second’ type of convert above. Or perhaps is the ideal a sort of synthesis of the three?

This article isn’t meant to be a ‘finished’ piece, but more of a rumination or a launching point for further thought.

What do you think? Tell me in the comments.

And as always, God bless. And keep me in your prayers.

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and Arabic full-time with no income, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies and my work. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!