Lent & Ramadan: Seasons of Faith

“Let us cleanse our senses and we shall see God.”

Alhamdulillah, if you are reading this, this means that if you are Muslim, Allah has blessed you to make it to another Ramadan — or if you are Christian, to yet another Lent. And what a brutal past year it has been for both Muslims and Christians living in Gaza, where much of life has been totally wiped out for good — neither homes, nor churches nor mosques nor schools nor hospitals were spared in the assault. This serves to remind us of the fleetingness of this life. We aren’t guaranteed another year — another day — another hour. Every minute and every second of our life is a gift from God.

And this, in many ways, is the great reminder of both Ramadan and Lent — the holy season in each faith of prayer, repentance, fasting, and turning back towards God.

It is not insignificant — for nothing is insignificant with God — that Ramadan overlaps with both Catholic and Orthodox Lent this year. Muslims, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians taken together make up over half of the global population. In this period of war, political strife, economic uncertainty, hunger and suffering, over half the globe is actively in a state of heightened prayer, repentance, and drawing closer to God in this season.

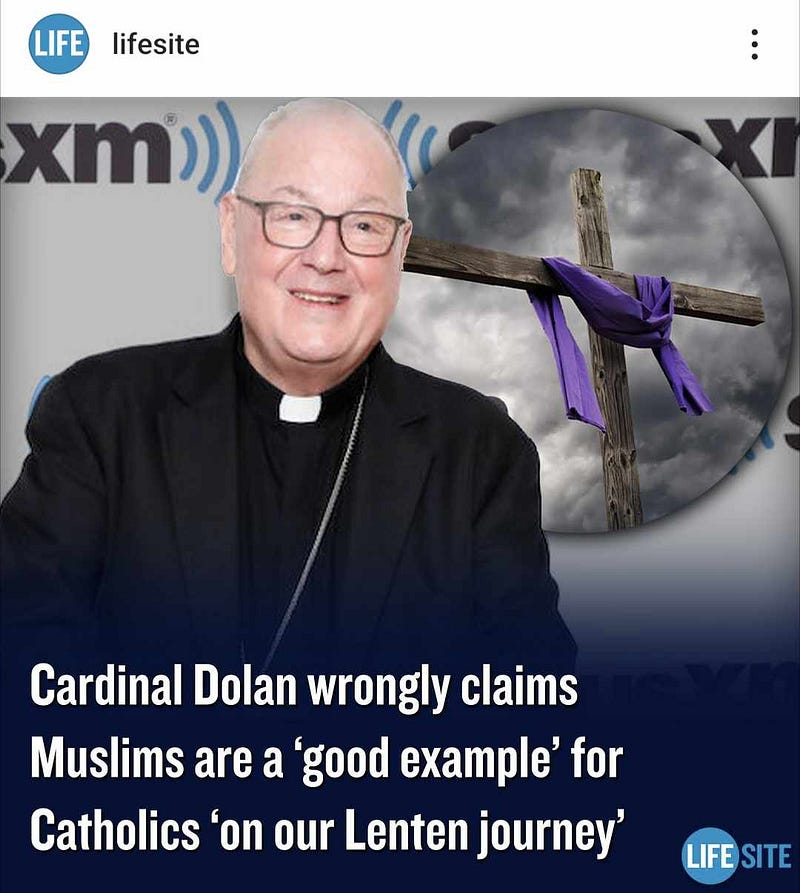

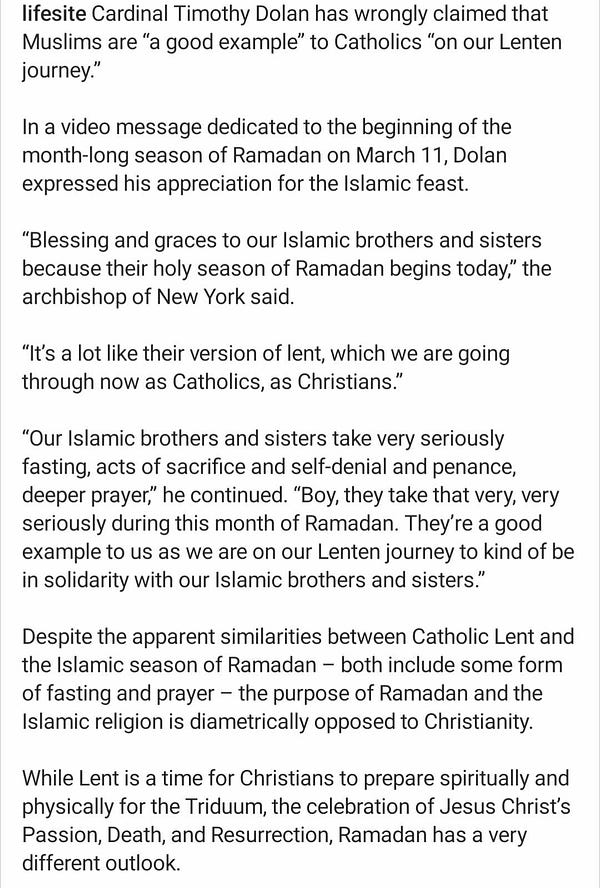

And yet, for some reason, there has been a larger than usual amount of vitriol online comparing Lent with Ramadan. Much of it is coming from various trad/conservative Catholic sources. A Lifesite news article, for example, ran a piece two days ago quoting Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who officially and very kindly greeted Muslims on the first day of Ramadan, saying: “Blessings and graces to our Islamic brothers and sisters, because their holy season of Ramadan begins today! They’re a good example to us on our Lenten journey.”

The Lifesite News article explains the “secret” and duplicitous “real meaning” of Ramadan by quoting “Islamic scholar” Robert Spencer, who says: “Ramadan is a month in which Muslims are to redouble their efforts to please Allah… The highest form of service to Allah, according to Muhammad, is jihad, which principally involves warfare against unbelievers.” He concludes: “Murdering infidels thus doesn’t contradict the spirit of Ramadan; it embodies it.”

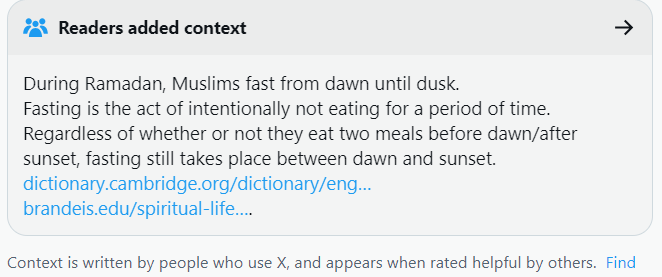

For good measure, the Lifesite article continues with quotes by notorious Islam-obsessive David Wood, who posted the comment below, helpfully explaining: “Reports and studies have shown that Muslims often report weight gain and digestive problems due to overeating during the month of Ramadan.”

Thankfully, X users have added an explanatory note to David’s post:

I don’t wish to give either Lifesite News nor David Wood any more attention than they are worth, but I just wanted to highlight a little bit of the vitriolic and wild accusations that paint such a fantastically distorted picture of the practice and tradition of Ramadan. It is unfortunate, because many people read these accounts from “Islamic scholars” like Spencer and Wood and adopt them uncritically with no real experience with actual Muslims — and sadly, much of the ‘conversation’ online regarding Ramadan in Christian circles reflects this.

That said, I’d like to reflect a bit on the real meaning and understanding of Ramadan and it’s comparison to Lent in both the Catholic and Orthodox traditions.

Comparing Traditions: Ideal vs. Actual

When we talk about religious traditions, we need to distinguish between the ideal practice of that tradition, as opposed to the actual practice of it. The tradition of Lent in Christianity goes back to the very first centuries of the Church. While it has been preserved to varying degrees in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, it has largely been jettisoned within Protestantism. As such, I have overlooked Protestantism in this article.

The Tradition of Ramadan

One can find the genesis of Ramadan is in the early years of revelation given to the Prophet (ﷺ). It was revealed in the Quran the institution of the Holy Month of Ramadan — a time set apart for God, for fasting, for prayer, for Quranic recitation, and — importantly — a time for community.

Fasting was certainly not invented by Islam. The Quran states: “You who believe, fasting is prescribed for you, as it was prescribed for those before you, so that you may be mindful of God.” (2:183) Fasting has been a time-honored religious practice dating back thousands of years, as evidenced early on in many different religious traditions. One of the earliest mentions of fasting in the Bible occurs during a battle in the book of Judges. In this account, God gives both strategy and victory to the Israelite army after seeking the Lord in prayer and fasting. In the Christian tradition, the Lenten fast mirror’s not only the Israelite’s forty year sojourn in the desert, but Christ’s forty days of prayer and fasting in the desert which preceded his public ministry.

During the month of Ramadan, Muslims fast every day from dawn to sunset. Well before the rising of the sun, Muslims will eat the first meal of the day, which is meant to hold you through until sunset. This meal usually includes lots of high-protein foods, water (for hydration) and coffee (because it’s really early). Then, after the dawn prayer (‘Fajr’), there is no food or drink whatsoever until sunset. At sunset, the fast is usually broken with a date and a little water or milk before the sunset prayer (‘Maghrib’), and then a larger meal is eaten after the prayers. It is customary to break the fast communally. Breaking the fast is a joyous occaison combined with prayer and, later in the evening, Quranic recitation.

What is often overlooked and misunderstood by non-Muslims is the very communal nature of the entire month of Ramadan. One is not merely fasting or praying on their own during Ramadan, but in a very real way Muslims are actively fasting and praying together and in union with the entire global body of Muslims — the Ummah. While religious observance tends to vary regarding the practice of Lent in Christian churches, a full 80% of Muslims globally and in the United States report fasting during Ramadan. During the day, Muslims support and encourage each other in their total fast, and during the evenings and into the night, Muslims — as a community and within their families — partake in joyous meals, special prayers, spiritual talks and conversations, Quranic recitations, night prayers and prostrations, and so forth. During Ramadan, one truly gets a sense of being one within the fold of a great spiritual community of Muslims — a true family of faith and brotherhood of believers.

It is certainly true that one can approach the Ramadan fast mechanically, lackadaisically, or for the wrong reasons. The fast and the prayers can be done legalistically, and the feasting in the evening and at night can become an exercise in gross over-indulgence. But approaching the month of Ramadan in this way goes against the spiritual discipline of Ramadan as it has been prescribed, and it squanders the spiritual rewards and merits that we receive in our fasting and discipline. When we are given all of these tools to draw closer to God, it only harms ourselves if we neglect or misuse these tools, or if we direct them towards filling our own desires — whether it is the desire for food, or the desire to be seen as a great faster (spiritual pride), etc.

There is one particular difference that can be pointed out between Muslim fasting and fasting within the Christian tradition. While fasting is seen as essentially a spiritual tool to help strengthen the believer, in the Islamic tradition, fasting is seen as something a bit more than this — it is a gift for Allah Himself. A well-known hadith says:

The Prophet (ﷺ) said, “(Allah said), ‘Every good deed of Adam’s son is for him except fasting; it is for Me. and I shall reward (the fasting person) for it.’ Verily, the smell of the mouth of a fasting person is better to Allah than the smell of musk.”

Fasting, for a Muslim, is an obligation from God Himself, as a gift and an offering directly to Allah. This is revealed in the Quran. This doesn’t mean, however, that a Muslim slavishly fasts out of fear of the wrath of God. On the contrary, it is a joy to enter into this period and practice of fasting, not simply because the rewards of fasting are so sweet, but because the practice itself elevates and cleanses the spirit of the person who fasts with the right intentions, with prayer, and with the love of God.

Orthodox Christian Lent

Having experienced both Roman Catholic and Orthodox Lent, it is very easy for me to see the similarities between Lent and Ramadan. Of all of the Lenten traditions, the tradition that feels closest to Ramadan, for me, is the tradition of “Clean Week” — especially as it is practice in monastic communities. “Clean Week” is the first week of Lent in the Orthodox Christian tradition. During Clean Week, church services can be very long (sometimes up to seven hours at a time!) and the fast is near total much of the time. In the Greek tradition, there is a total fast for the first three days of the week with no food or water at all, while in the Russian tradition, there is a total fast every morning until noon, where a very light meal of simple, uncooked foods is eaten, with liquids permitted the rest of the day. “Clean Week” is meant to be that: a week in which one is ‘cleansed’, spiritually and even physically, through a staunch regimen of prayer and fasting. During this week, the fasting can be difficult, but one really does feel cleaner, lighter, and one’s prayers sharper and more focused.

Throughout the rest of Orthodox Lent, the focus in fasting is not so much in the amount of food that is eaten (though moderation is always recommended), but rather the obligation is in the type of food consumed. That is, Orthodox Christians abstain completely from meat and animal products, which includes eggs, milk, and dairy, as well as most oils. Alcohol is also not consumed.

There is a communal element in Orthodox Lenten fasting as well, in that all Orthodox Christians partake in the same fasting and abstention rules while also observing, communally, the Lenten liturgical feasts and holy days, along with the extended Lenten private and liturgical prayers. A particular beloved tradition in the Orthodox Christian Lenten practice is the recitation of the Orthodox faithful of the prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian, which reads:

O Lord and Master of my life, a spirit of idleness, curiosity, ambition, and idle talking; give me not.

But a spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love, bestow upon me, Thy servant.

Yea, O Lord King: grant me to see mine own failings, and not to condemn others; for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages. Amen.

This prayer is recited by Orthodox Christians at every church service during Lent, as well as privately. Orthodox Lenten practice has remained relatively unchanged since the early centuries of the Church. Reading this prayer now, there is hardly anything objectable here from an Islamic point of view.

Roman Catholic Lent in Modern Practice

The Roman Catholic tradition of Lent has, in modern practice, regrettably lost much in the way of tradition and observance — both in personal and liturgical practice. While the Roman observance of the Lenten fast was once very rigorous and looked similar to the current Orthodox Christian practice, almost all of it has gone by the wayside. Fasting during Lent, for most Roman Catholics, amounts to abstaining from meat on Fridays and eating fish instead — and even this usually observed by only the most ardent faithful.

The most tragic loss in the Roman Catholic Lenten tradition is a loss of the communal element. With the exception of some traditional Latin Mass Catholic communities, Lenten fasting is largely unobserved, and has popularly been replaced with the individualistic and idiosyncratic practice of “giving up” something during Lent. While ‘chocolate’ is the temptation that is often the most popular thing abstained from, I’ve heard of people ‘giving up’ anything ranging from coffee to gossiping to Instagram to nail biting to fast food… and anything and everything in-between. In college, I once heard a fellow (unmarried) college student openly and solemnly declare that she was “giving up sex” for Lent, apparently seeing no deeper issues with this declaration. In essence, any serious and communal practice of ascetical renunciation in order to ‘cleanse one’s senses’ in order to draw closer to God is lost and is instead replaced with idiosyncratic tokens of symbolic self-denial.

One element of traditional and communal Roman Catholic Lenten observance has remained, however, and that is the liturgical observance of Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of the Roman Catholic season of Lent. It is on Ash Wednesday that Roman Catholic faithful receive the iconic cross of ashes upon their forehead while the priest says the words: “Remember that thou art dust, and to dust thou shalt return.” This is a solemn and reverent remembrance of our own mortality.

In light of the paucity of contemporary Roman Catholic Lenten practice, Cardinal Dolan’s words to Catholics regarding the seriousness with which Muslims take Ramadan makes sense. The Catholic West has a rich Lenten history and tradition, and they would only need to recover their own traditions which have been lost, forgotten, abrogated or obscured over time.

Conclusions

In light of traditional Roman Catholics accusing Cardinal Dolan of a sort of religious relativism, I also do not want to appear to place all religious traditions on par with each other or to suggest that our doctrinal differences don’t matter. They do. However, I do want to say that it is simply wrong to say that fasting during Lent and fasting during Ramadan have purposes that are “diametrically opposed”. To say such a thing is not simply willfully ignorant, but it is a blatant lie — no matter what such a person saying such things may personally believe. While there are Muslims, Catholics, Orthodox, and religious believers of any kind who may approach the faith wrong-headedly or with a less than pure intention, it is the general striving of all believers of good will to work together and to lift each other up in drawing closer to God. This is done through the common religious practices of fasting, prayer, and ascetical self-denial. We have certain fasts and certain seasons in which this drawing closer is more intense: Ramadan for Muslims, and Lent for Christians. And we have feasts and Holy Days in which we rejoice, communally, for what God has done for us. Whatever differences we have, doctrinally, we at least have this in common. And we can at least recognize the sincere struggling in the faith of our fellow Christians/Muslims in good will and in striving to greater love and draw close to God. We all have very rich traditions from which we draw from, and the denigration of the ‘other’ really does nothing to lift up own own practice.

As Muslims, we remember that it is revealed in the Quran:

And thou wilt find the nearest of them in affection to those who believe [to be] those who say: Lo! We are Christians. That is because there are among them priests and monks, and because they are not proud.}* (Al-Maidah 5:82)

There are among the Christians those who are not far from our Muslim faith in their love of God. For it is deep within the heart of every person a primordial yearning for God — no matter how that yearning may be obscured over time. May we use our prayer, our ascetical self-denial, and our fasting to be for a greater increase of love — love of God and love for our neighbor/brother. For in a mystical way, the closer we draw to God, the closer we draw to each other.

Please pray for me, a sinner, and forgive me if I have mispoke in any way. Have a blessed Lent, a fruitful Ramadan, and alhamdulillah for all things!