Moving Forward

When I was a teenager, I was a fan of Radiohead. As a kid of a divorce living in the later years of the 20th century, their sounds and lyrics lamenting modern alienation, malaise, and ennui appealed to my introspective and vaguely apocalyptic mood. This general sentiment was in the air, with films like Fight Club, American Beauty, Office Space, The Matrix, and Eyes Wide Shut topping the box office charts in 1999 — the year I graduated high school. All of these films, in their own way, dealt with the banal unreality of American life in the later 1990s. This sense of brooding was perfectly encapsulated in the words of the fictional character, Tyler Durden, in Fight Club — a film that feels only more relevant now with the passing of time: “We’re the middle children of the history man, no purpose or place, we have no Great war, no Great depression, our great war is a spiritual war, our great depression is our lives.”

Fitting nicely in this era and sentiment was Radiohead’s masterwork breakthrough and critical success, OK Computer. It is an album that dealt with all the same themes as the films above — modern alienation, cynical politics, loss of meaning, empty commercialism, vapid consumerism, etc. Though the album never garnered the air play that, say, the Spice Girls or “Barbie Girl” did in the same year, the album was enough to propel Radiohead into superstardom overnight. As Radiohead’s frontman, Thom Yorke, would recall, the band went from playing small clubs to massive sold out arenas overnight. They were a one-hit-wonder band with Creep, and now, all of a sudden, they were thrust into international fame.

Nobody was more surprised by this turn than the band themselves. In the dizzying blur of tours, interviews, radio plugs, and TV appearances, Radiohead had become a victim of their own success. Yorke, along with the other band members, did not know how to handle this new-found acclaim. “I had a series of mini-breakdowns where the public persona — this thing, this face, this person who writes this music… I would walk past that person in the mirror or listen to that person playing guitar and I didn’t know who they were,” reflects Yorke of this time.

In 1998, they would release a film entitled Meeting People is Easy. In perfect late-90s fashion, it documented the alienation and overwork that was the result of the success of their album lamenting alienation and overwork. The following dialogue from Meeting People is Easy captures the hole they suddenly found themselves in:

(Unnamed) “There’s a line in Karma Police about he buzzes like a fridge. And to me, when you’re driving around in America and you have the alternative stations on in the background or in your hotel room or whatever; and it’s just like a fridge buzzing. That’s all I’m hearing. I’m just hearing buzz. It’s really odd. It’s kind of funny though really. You just have to laugh.”

(Interviewer) “But one song that you had that was obviously really embraced — “

(Unnamed) “Yeah, that had the fridge buzz in it.”

(Interviewer) “ — with the modern rock format, was Creep. I mean you first came in with that.”

(Unnamed) “Yeah, that was a good fridge buzz.”

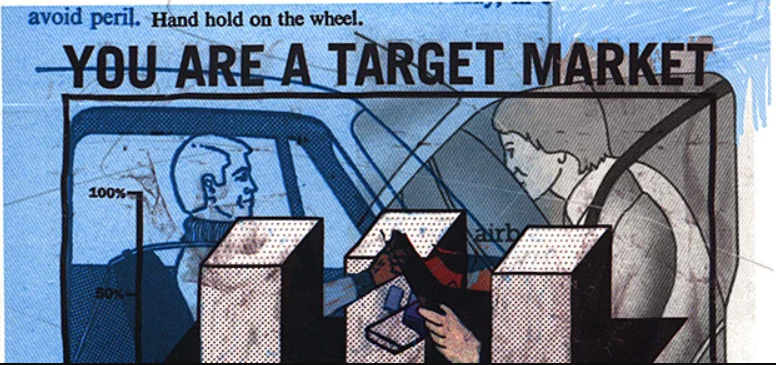

(Unnamed) “The trouble with a lot of music in this country is the radio stations with modern rock. It’s such a stail format. As far as I can work out and we can work out as a band is, the music they put on these stations, it’s not for the people. It’s to satisfy the advertisers. It’s completely reactive as opposed to proactive.”

(Unnamed) “You’ve got a “Teletubbies” watch on.”

(Unnamed) “Tower, lobby, floor. Tower, lobby, floor.(Long pause) Tower, lobby, floor.”

(Radio Presenter) “You both look remarkably healthy.”

(Unnamed) “I’m talked out; I’m a vacuum brained bimbo.”

(Unnamed) “You know, last year we were the most hyped band. It’s bollocks.”

(Interviewer) “Do you expect any particular action of your audience?”

(Unnamed) “I’m terrified.”

(Interviewer) “Why?”

(Unnamed) “Well, just cuz you know. Saying — just coming back. It’s sort of quite terrifying. And just going into the whole — the wheels start turning again and the industry starts moving again. This time they get more terrifying and it just keeps going and it’s basically outside of our control.”

(Unnamed) “You will become a hypocrite. You’ll become a liar. You’ll try and paper-up your own cracks and — you know. And everybody does it. And that’s what being an adult is. And then you have babies and — that’s it.”

On its surface, it is a rather grim view. But on a deeper level, there was a sense of the band wanting to remain genuine in the face of the lure and the Siren’s Song of fame. There was a sudden expectation thrust upon the band. To produce what sells. To please the audiences. To appease the marketers. What direction would they decide to go from here? How would they move forward? Would they sell out? Would they follow the fame and money, as many people do? Or would they retain their soul in the face of success? This fame and this tension nearly led the band to collapse. They would not release another album for some three years — eventually releasing Kid A in 2000, which was one of the most epic about-faces in musical history.

It was Kid A in 2000 that brought the band back from the brink of destruction. In the end, they chose to decide their own direction and follow their own creative impulses in the face of commercial success, come what may. And this is what made Radiohead not only a great 90s band — but one of the greatest musical forces of a generation. Even without the radio play — which they never truly had.

So why would I talk about Radiohead here?

In a certain sense, it is a parable. And something which I have experienced myself, in a much smaller way. How will I move forward?

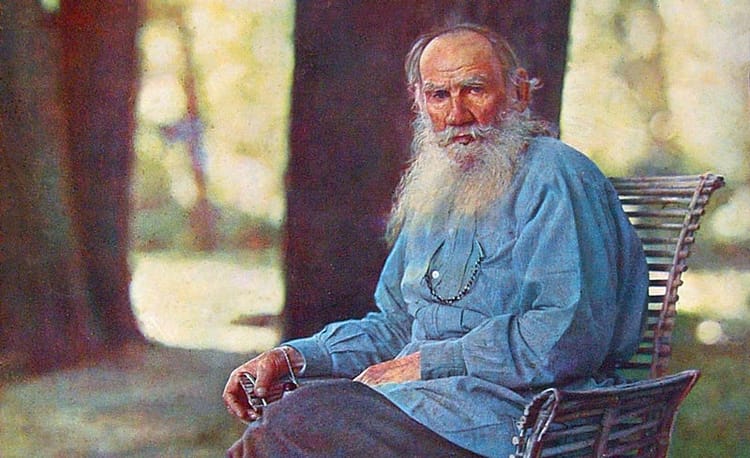

Literally overnight, I have gone from a monk in the mountains of California into a sort of stardom in my conversion to Islam. (My very sincere conversion to Islam.) While much of the media hype has died down since the news broke in late February, mostly due to my purposeful refusal to fan the flames with interviews and appearances, I still feel a responsibility to be a sort of mouthpiece and figurehead just given my situation. Though it certainly happens more often than people may realize, it is not everyday that a priest converts to Islam. Especially a priest-monk, for that matter. And while I have made a sort of name for myself by being an advocate for traditional religion as well as making myself available to people as much as I can, pastorally, there is really nothing interesting about me right now, in my estimation, other than my own conversion. I haven’t written any books. I’m not really a public figure. I was certainly not a ‘top priest’ in the Church, as many media reports have claimed. I’m really just a man struggling to get by, working on my own salvation in my own flawed way.

But the Siren’s Call to fame is real. I was working at a pizza shop and deli when the news came to me that I was the top trending Google search in the Arab-speaking world. I have been invited to symposiums at Cambridge and to tour Turkey. (I still need to renew my passport before I can go anywhere.) And there is the allure of the daʿwah scene online— to give witness to Islam. I could pose as a superstar in that arena, if I wanted to. But I know, if I am honest with myself and others, that I am not ready to do that. Not because I don’t want to or that I don’t think this is something generally important, but because I know that I am not ready for such a thing. To do otherwise would be motivated by a kind of self-important egoism. The nafs in Islam. At what point am I promoting myself over God?

While I may have been a sort of authority in Christianity, I am still just a baby in Islam. After all, my initial goal was to leave the public eye, in a sense, and quietly live my life and work on my own faith and salvation in Islam. It is my own fault that I never really figured out how to do that, and thus the explosion of 15-minute fame I received in late February. Part of this seeking of privacy was also in a sense of not scandalizing those who have looked up to me in the past as just the type of ‘elder’ that many in the Muslim world are now seeking in me. As a recent conversation with a trusted Muslim friend and scholar have confirmed, my authority in Christianity does not transfer into an authority in Islam. Even after reading about Islam for twenty years and researching the Faith, I realize now that I barely know anything compared to what there is to know. And not just ‘know’, but put into practice. The faith of God in a man is, ultimately, a mystery of the human heart. To exploit that for any reason is to cheapen it. To make it something other than it ought to be. To go astray.

It is the lure of the world.

I have seen many men shipwrecked in the Church by this sense of exploitation. Either for power. Or for fame. Or for ideology. Or for politics. Or even for money. I don’t want this to follow me into Islam.

This has been my question moving forward. How to balance this tension. This sense of a certain responsibility, coupled with a healthy attitude towards the Faith and towards my place in it. Some people have remarked with concern my seeming silence after all that has gone on in the past months, asking if I am okay — which I truly appreciate. Even some Catholic friends have suggested that I “run with it” and use the fame to my advantage. But I feel that it is playing with fire. The nufs, again. When we search for God, nothing should get in the way. My initial entry into monastic life in 2009 was just such a search for God in blessed obscurity, but at some point that had gone awry.

The beauty of Islam is, in part, that we are all the same. We all face the same direction in prayer. We are all brothers. We are all one ummah. There is no priest or cast or race or hierarchy — even in Islam. If a priest converts to Islam, he is your brother. I stand shoulder to shoulder with anybody and everybody in the masjid. I wear no distinctive clothing. I have no titles. We are all striving together. And the beauty and the hospitality I’ve seen — and received — in Islam is something like I’ve never known before.

If I am to witness in Islam, I wish to witness in this way — as your brother. And nothing else. As an honest man — if not a flawed man — working and praying along side you as a brother. All glory belongs to Allah. To God.

This brings me back to the Radiohead analogy. The world will allure you to the brink of destruction, but we must never follow the world, no matter how good the intentions. It is always our decision who we are.

“You can try the best you can… the best you can is good enough.” If our striving is truly sincere, then God will do the rest.

May Allah make it easy on all of us.

Alhamdulillah. Glory to God for all things.