My Personal Mottos: An Explanation and Reflection

There are a few personal mottos I’ve adopted (and retained) over time. Here is a brief explanation of them:

𝟮𝟬𝟬𝟰: 𝗤𝘂𝗼𝗱 𝗦𝗶 𝗡𝗼𝗹𝘂𝗲𝗿𝗶𝘁

This is taken from Daniel 3:18 from the Vulgate: Quod si noluerit, notum sit tibi, rex, quia deos tuos non colimus, et statuam auream, quam erexisti, non adoramus. (“But if not, be it known unto thee, O king, that we will not serve thy gods, nor worship the golden image which thou hast set up.”)

“Quod si noluerit” translates to ““But if not…”

In Daniel 3:18, “but if not” refers to the statement that even if God does not deliver Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the fiery furnace, they will still not worship the golden image set up by King Nebuchadnezzar, declaring their unwavering loyalty to their God above all else; essentially saying, “we will not compromise our faith, even if it means facing death.”.

It is interesting that this has remained a constant theme in my life: Never bow a knee to idols. This can be in the most literal sense — as in the Muslim concept of shirk. Or it can be in the most subtle of senses in which we sell ourselves out or put anything before our Highest Ideals. (And certainly not before God.) This could take the form of cowardice, or fear, or lust for money, or power, or fame… the bowing of our highest ideals and aspirations towards our baser desires, or ego, or ‘the world’ (dunya).

I was struck by this line in the Bible after learning of the amazing account of the “Miracle of Dunkirk”. (I urge you to read the account in the preceding link.) The simple line “But if not…” was once readily recognizable to an English population still deeply steeped in Biblical literacy and awareness… but which now, unfortunately, has sold his birthright for a mess of pottage.

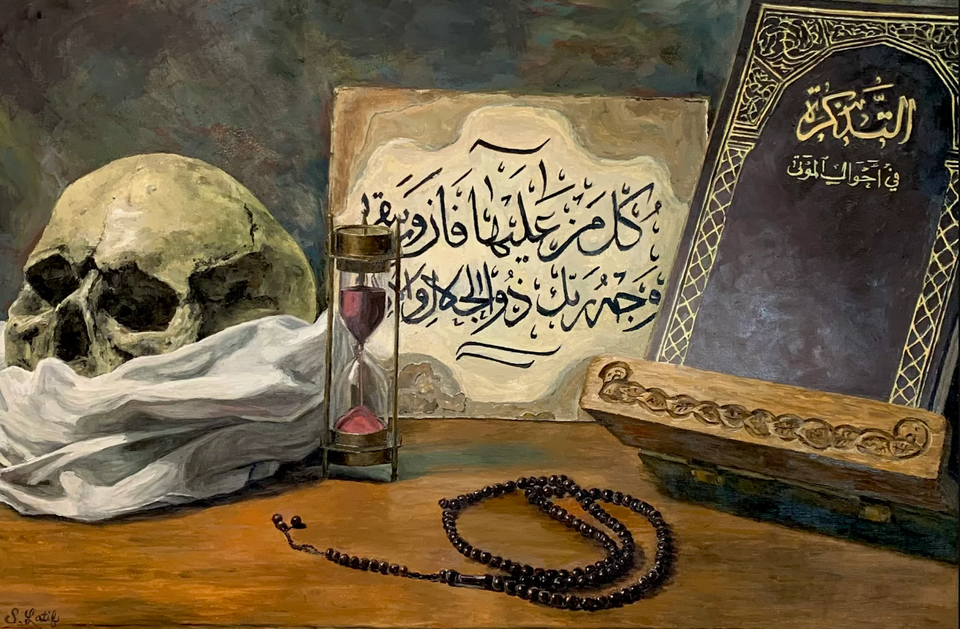

𝟮𝟬𝟭𝟰: 𝗗𝗶𝘀𝗰𝗶𝘁𝗲 𝗠𝗼𝗿𝗶

“Discite Mori” I borrowed from a painting that I first saw in 2014 entitled Fantasy Interior with Jan Steen and the Family of Gerrit Schouten. It was painted by the artist Jan Steen in 1660. Google Arts describes the work in this way:

Jan Steen was known for his scenes of bawdy revelry, often with moral overtones. Here we see him dressed as a gentleman, gesturing towards a seated man who has recently been identified as Gerrit Schouten, a brewer from the Dutch town of Haarlem. Schouten, accompanied here by his son and daughters, owned a brewery called the Elephant. Steen creates a witty allusion to this fact by placing a painting of an elephant over the fireplace. Centered on the mantelpiece is a skeletal bust of Death, inscribed with Discite Mori (Learn to Die). This reminder that the pleasures of life are fleeting and that death will ultimately triumph is tempered by the inscription on the harpsichord: musica pellet curas, or music drives away care.

At the time I came across this painting, I was reading Marcus Aurelius and a great deal of Stoic philosophy, and I was attracted to the related concept ‘Memento Mori’, or remembering death. “Remember that thou art dust… and to dust thou shall return.”

Upon seeing ‘Discite Mori’ or ‘Learn How to Die’ in this painting, I felt that I had struck upon something. “Memento Mori” always seemed very passive to me. As Christians, we were always called to ‘die to ourselves’ and to ‘take up our cross’. This is a very active endeavor. Something that you must struggle to do. In contrast , I saw ‘Discite Mori’ as a sort of more active “Memento Mori” and a “Being-towards-death” in the Heideggerian sense.

The more I read into Heidegger, the more I realize that he had the same idea. Heidegger’s concept of “Being-towards-death” (Sein-zum-Tode) comes from Being and Time and is central to his existential analysis of human existence (Dasein). It refers to the way in which human beings relate to their own mortality, which Heidegger sees as fundamental to authentic existence. Being-towards-death means living with an awareness of one’s own mortality in a way that pushes one towards a more authentic, self-determined existence. For it is paradoxically only when we learn to die do we truly live.

Unless a grain of wheat falls and dies in the ground, it remains alone, but if it dies, it yields much fruit. (John 12:24)

Of course this also carries over into the Islamic tradition. There are many possible quotes to cite here, but a quote often heard in the Islamic world which is attributed to the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) is this: “Die before you die.” This is the way of true life.

𝟮𝟬𝟮4: “𝗜𝘁 𝗶𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗯𝘂𝘀𝗶𝗻𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗳𝘂𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗲 𝘁𝗼 𝗯𝗲 𝗱𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲𝗿𝗼𝘂𝘀.” 𝗔𝗿𝗲 𝗪𝗲 𝗗𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲𝗿𝗼𝘂𝘀?

"It is the business of the future to be dangerous” is a quote from the 20th century philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. This quote reflects his philosophy of process and change, emphasizing the inherent uncertainty and dynamism of reality.

Whitehead was a ‘process philosopher’, meaning he saw reality not as a collection of static things but as an ongoing flow of becoming. In this context, the future is not a predictable, stable extension of the present — it is an open, creative field of possibilities, which by its nature, carries risk, upheaval, and transformation.

I have always found this quote to be intriguing and iconic… and we have to ask, in fulfillment of this ‘challenge of the future’… Are we dangerous?

In other words, are we living up to the challenge and the demands of facing the future head on? With boldness? With bravery and firmness? With uncompromising resolve?

As it has been said: The future belongs to those who show up.

To quote Deleuze and Guattari: “The question is not: is it dangerous? But: how far can we take the risk?”

Or Nietzsche: “The secret of the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of existence is: to live dangerously!”

Or Muhammad Iqbal: “If you desire to rise, create a disturbance in your existence.”

Or Al-Junayd al-Baghdadi: “A true warrior youth (fatā) is the one who throws himself into danger for the sake of truth, not the one who clings to safety.”

Or Imam Ali (RA): “Meet your fate with a sword in your hand, rather than wait for it to come to you.”

Or Nizam al-Mulk: “If you seek safety, you will become a slave. If you seek honor, you must ride into the storm.”

Or Ibn al-Farid: “The fire that you fear is the light that will purify you.”

Now is not the time for pusillanimity and timidity. It doesn’t mean we should be belligerent with others. We must do everything with good character — with refinement, good manners, decorum, decency, humaneness — or adab (أدب). And yes, we must do everything with love… but love is bold and demands action.

May God grant us the courage to face the future with a boldness befitting men of faith. May we never compromise ourselves and our souls with the false peace of this world… and with the spirit of Dajjal.

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language full-time, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!