The ‘Muslim Priest’: An Introduction (Part 4)

بِسْمِ اللَّهِ الرَّحْمَنِ الرَّحِيم

In the first three installments of this brief spiritual autobiography, I explored my early spiritual formation. I had walked away from a possible conversion to Islam in my early 20s and instead chose to remain within the Christian milieu as an Orthodox Christian. Even during my time as an Orthodox Christian, however, my pull towards Islam persisted as I continued to study the faith. In this installment, I shall begin to explore the final year leading up to my embrace of Islam.

Texas

In November of 2021, I packed up my Ford Escape, said farewell to Milwaukee, my adopted home, and made my way down to Texas. It was there that I spent some time visiting family as I worked on our project which sought to form a traditional monastic community. My move to Texas was full of optimism and hope — which was very quickly dashed upon my arrival. Assurances of support within the Church came to nothing, and I entered the Christmas and New Year season essentially stranded in the Lone Star State — staying in a spare room at my mother’s house in West Texas. My sense of despair and depression was deep at that point — something which I have never truly felt before. Where was I to go? What would 2022 bring? It was difficult to say.

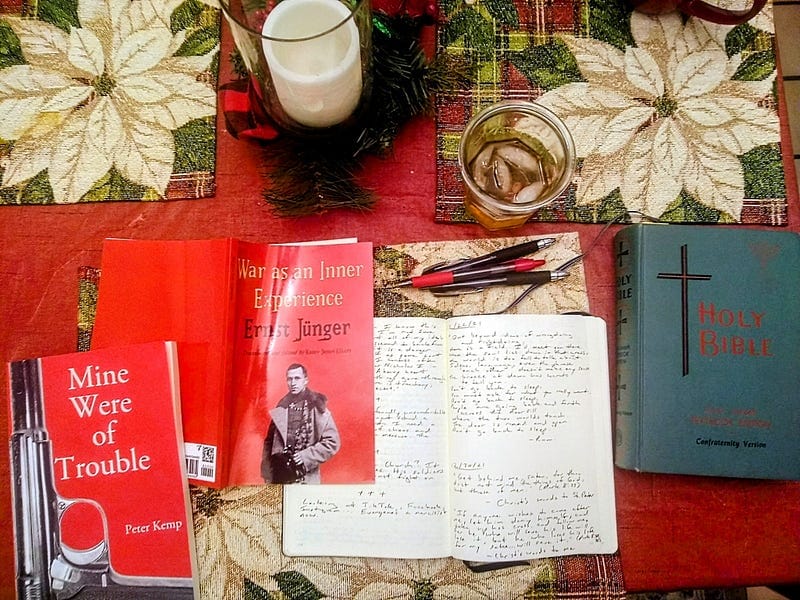

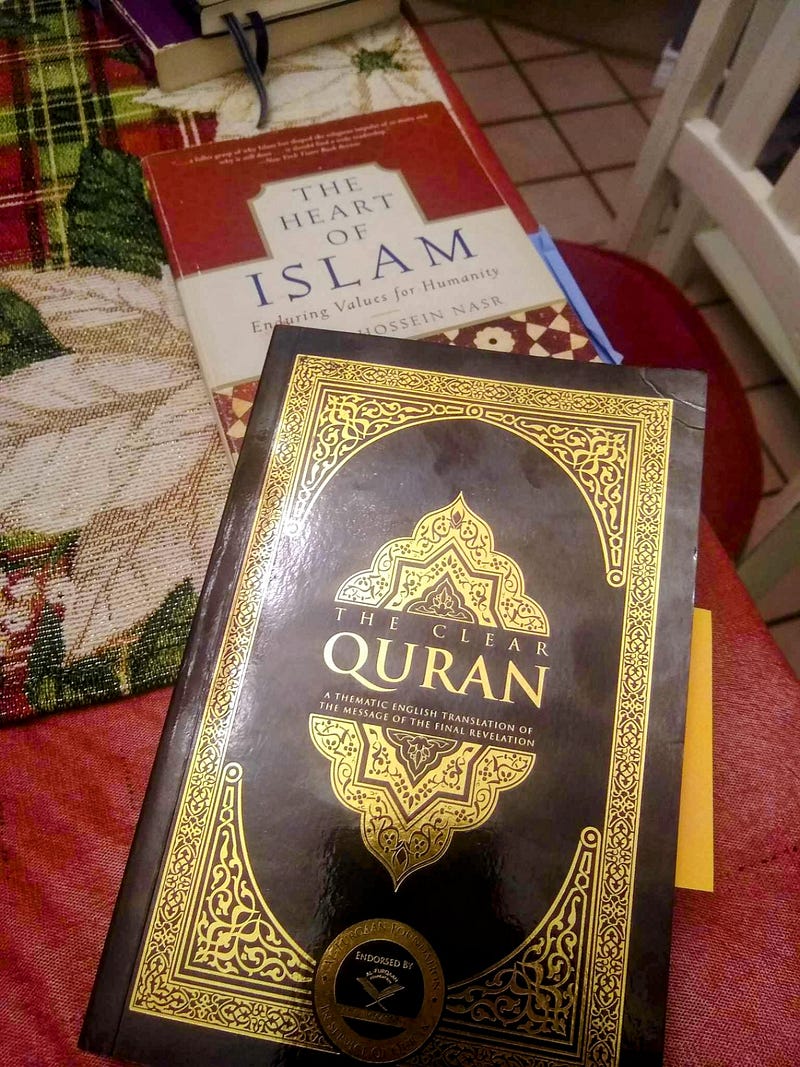

In the meantime, I continued to read. I read about Islam, certainly — but I also delved deeply into history, politics, philosophy, literature — Ernst Jünger, Nietzsche, Gene Wolfe, Ernst Niekisch, Orthodox Christian Patristic theology, Vladimir Soloviev and Sophiology, religion in Russia, the history of Bin Laden and the Iraq War, Carl Schmitt, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian… etc., etc. I tend to approach matters holistically. No aspect of life exists in a vacuum. There is always an ongoing interplay between politics, philosophy, religion, culture, art, history, and so on. As such, the confluence of all of these things through history has brought us to our present moment. Christianity does not exist apart from a people, a history, culture, politics, etc. And neither does Islam. To discover how all of these various things interplay and fit together has always been one of my passions in seeking understanding. I have, since I was a young boy, always sought a sort of ‘Unified Field Theory’ in life and in the world we live in. The ‘One Principle’ and Truth that holds all these various things together.

In my reading, I happened upon some very interesting accounts of former American veterans who took part in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. When they spoke about Islam, I was surprised to see how many of these vets spoke so highly of the Islamic faith and of the good character of the Muslims that they encountered. Many of these vets went in to war in order to ‘fight the Muslims there so that they wouldn’t have to fight them here’, to quote the Bush administration at the time. However, once they spent some time in Iraq and Afghanistan, the faith and good character of the people they were fighting left an impression on many of them. Some of them, even, would end up embracing Islam themselves. Reading some of these accounts left a deep impression on me. It was after first-hand experience with Muslims that often lead people to change their minds regarding Islam, it seemed to me.

California

In February of 2022, I flew to California at the generous invitation of a very kind and saintly abbot (may God grant him every blessing!) to make an extended and open-ended visit at his monastery. After a frustrating few months in Texas, this move was a very welcome one. Indeed, I would be back home in a monastery once again.

What follows here I feel is very difficult to summarize in just a brief article. (At some point, perhaps a book-length treatment of the subject is in order.) It was in California that all of the various strands of thought and inner inclinations over the years came to quick fruition, and my path to Islam became more clear. And I remember how surprisingly quick everything occurred once I was there. It was as if, for many years, I had been struggling to untangle so many knots — knots that have caused me so much real anguish and anxiety. And then, all at once, as if with one pull of a string, these knots simply fell away. By the grace of God. And perhaps with a little solitude, prayer, and the fresh California mountain air.

I kept extensive notes in my journal over this period. A large portion of my notes were taken listening to the talks of Abdal Hakim Murad. I found hours of his talks on YouTube and would listen to them attentively. By the summer of 2022, I began to think of Abdal Hakim Murad as my teacher.

It was also during this time that I discovered the deeper connection between traditional Islam and tasawwuf, or Sufism. The dichotomy that I perceived as the ‘outer’, or ‘exoteric’, practice of Islam and the ‘inner’ or more ‘spiritual’, ‘esoteric’ understanding of Islam in Sufism all of a sudden collapsed into one unified whole as I began to better understand Islamic history and tradition.

It was during this time that I discovered the ‘Akbarian tradition’ of Ibn Arabi, whom I grew to love. I began to see the world through his eyes. Ibn Arabi’s Christology I found particularly intriguing. To him, Christ was a Prophet, yes. But more than this, he was something of a Theophany — an Opening to God — a Gateway into the Sufic Path.

A large problem I had been working through within the Christian tradition was the seeming slide of much of Christianity towards an a-history of loss of tradition and into something that seems not much different from contemporary secular liberalism. Where did this come from? From whence did this emerge? It was my thinking for a long time that this was simply Western Enlightenment principles seeping their way into the Church and into Christianity. These were forces unleashed by the dual revolutions of the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation in Western Europe. These forces were contrary to the faith, in my estimation, and I felt that there needed to be a strong counter-force opposing much of this trend which had eroded (and still erodes) the traditional faith and leaves nothing but an empty husk of post-modern subjectivism.

What seemed to be a rebirth of a traditional understanding (orthodoxy) and practice (orthopraxy) of the faith in the Catholic Church under Pope Benedict was quickly squashed by Pope Francis by various means. The direction of the Catholic Church under Francis was becoming increasingly clear as the years went on, and such lamentable events such as the Amazonian Synod of 2019 and the current Synod on Synodality only serve to introduce division and confusion into the Church. If the mechanisms which were put in place in the Church to secure the Deposit of the Faith through history become the very stumbling block for the faithful — then what does this mean for the Church?

It is not simply the Catholic Church which has problems. The problem is imbedded across the board within Christianity — with some holdouts within Eastern Orthodoxy, perhaps. There is generally within Christianity (and increasingly within society at large) a crisis of authority. Certainly the old questions of who or what is the final authority are at play — but even more than that, the very idea of authority (or of an authority) is beginning to break down. “Why do we need tradition when I have the Holy Spirit?” “Why do we need bishops when we have the Bible?” “Why do we need any of these things when we have modern science and modern psychology?” “Why do we need a Father when we have generations of patriarchy and oppression?” And finally: “Why do I need an authority at all when I am being true to my own authentic expression and understanding of myself?” As such, I saw much of the faith degenerating into a cacophony of subjectivism.

What’s more, I was beginning to suspect that what I was seeing was not an aberration from the Enlightenment or from somewhere outside of Christianity which had wormed its way in. Rather, it was beginning to seem that what I was seeing was in the very DNA of Christianity itself. I felt this in reading Tom Holland’s sweeping history of Christianity entitled: Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. In it, he argued that radical egalitarianism and revolution are at the very heart of the Christian faith and have been from the beginning. What we see now in Western secularism, liberalism and ‘woke-ism’ is simply a de-sacralized Christianity. Given this understanding, for example, much of Pope Francis’ call for ‘renewal’ fits perfectly within the chain of Christian history — a history of constant ‘renewal’ and revolution.

Along these lines, I had for some time been enamored with the idea of a certain sort of ‘Nietzschean Christianity’. Nietzsche was a tortured soul. A sort of ‘inverted saint’, in a way. While I don’t adopt his views wholesale, I feel there was a great deal of truth in much of what he said — and certainly in some of his criticisms of Christendom and the modern Western world. Leaving aside the concept of ‘slave morality’, I found much value in his discussion of ‘the Last Men’. These are people, according to Nietzsche,who settle into the banal comfort of safety and mediocrity rather than striving for the heroic and for greatness. I felt that much of what Nietzsche said of ‘the Last Men’ really fit the description of modern men and women — and I thought this especially true in the Church. I saw it wherever I went, and I despised it. All striving towards sainthood was watered down to ‘be good’ — or worse, ‘be relevant’. and relatable to the modern man. All ascetical struggle was shrunk down to things like ‘giving up chocolate for Lent’ or other rather useless and insincere tokens of what was once a robust piety within the collective tradition and praxis of the Church. And yet campaigns which sought to introduce a certain manly ‘virility’ within Church life just seemed to fall flat most of the time — as if applying cosmetic change to a much deeper problem. Essentially, wearing a tweed jacket while smoking a cigar and drinking bourbon with a rosary in hand in front of book shelves on your podcast/Instagram was not going to fix the issue — as well meaning as this may have been.

Shaykh Abdalqadir as-Sufi — a Scottish convert to Islam — put the matter succinctly:

Nietzsche, with his prophetic awareness — in an intellectual sense — foresaw this coming disaster… Man has been downgraded. He is now already ‘sub’. We have been made sub-human. So we must take the Übermensch as an Islamic duty, an Islamic call.”

Nietzsche’s own criticism and distain for Christianity was no secret, but he did have a certain respect for Islam, saying: “If Islam despises Christianity, it has a thousandfold right to do so: Islam at least assumes that it is dealing with men. . . .”¹

The Church — and Christendom — is in crisis. (And for the record, I’m not happy about this fact.)

It was not because of the thoughts above that I turned to Islam. My interest in Islam and my thoughts of the issues within the Church and within Western society ran parallel with each other. That said, there was a moment in early 2022 when a lightbulb went on for me. I began to realize that everything that I wished to see in Christianity was already ready-made and built into Islam. In Western Christianity, there is a stark loss of esotericism — of this deeper spiritual, hidden tradition. Yet here it is in full bloom in Islam. Similarly, there is a lost of Tradition, mostly in Western Christianity, coupled with the growing reign of subjectivism . Yet in Islam, one finds a depth of Tradition and an unbroken chain of transmission that goes all the way back to the source — the Prophet (ﷺ). In much of Christendom, we have a loss of ascetical virility, of heroism and of sacrifice. In Islam, we see this in abundance in the practice of tasawwuf, or Sufism. This is coupled with the idea of jihad — both the greater and the lesser jihad (or the inner/spiritual struggle along with the outwards struggle for the faith), which are really two sides of the same coin.

It wasn’t simply that I was seeing the ‘greener grass on the other side’ in regards to Islam. It was simply that I was beginning to find all of my inner longings and convictions reflected perfectly within the Islamic tradition. And again, I write all this in short-hand here for the sake of brevity. Each of the above points really deserve a full and lengthy treatment on their own. (This is a worthy project for some future date.)

It wasn’t even that I saw within Islam a total rejection of Christianity — and certainly not of what is good, true, and beautiful within the Tradition. Within the Quran, there are a number of places in which Christianity is spoken of with respect to the commonalities Muslims share with Christians. For example:

“Surely those who believe, and those who are Jews, and the Christians, and the Sabians — whoever believes in God and the Last Day and does good, they shall have their reward from their Lord. And there will be no fear for them, nor shall they grieve” (2:62, 5:69).

“. . . and nearest among them in love to the believers will you find those who say, ‘We are Christians,’ because amongst these are men devoted to learning and men who have renounced the world, and they are not arrogant” (5:82).

“O you who believe! Be helpers of God — as Jesus the son of Mary said to the Disciples, ‘Who will be my helpers in (the work of) God?’ Said the disciples, ‘We are God’s helpers!’ Then a portion of the Children of Israel believed, and a portion disbelieved. But We gave power to those who believed, against their enemies, and they became the ones that prevailed” (61:14).

In the lines of poetry of Sufi mystics and great theological figures such as Ibn Arabi, we find beautiful words such as these:

My heart has become able

To take on all forms.

It is a pasture for gazelles,

For monks an abbey.

It is a temple for idols

And for whoever circumambulates it, the Kaaba.

It is the tablets of the Torah

And also the leaves of the Koran.

I believe in the religion

Of Love

Whatever direction its caravans may take,

For love is my religion and my faith.

While there is a criticism of aspects of Christianity within my own thoughts, as well as within the doctrines of Islam, an embrace of Islam is not a total rejection or condemnation in any sense. Even the miracles which I had personally witnessed in the Church were seen as signs of God’s loving grace towards all believers of good faith — and especially lovers of Jesus and his Virgin Mother, whom Islam also believes to be pure and a virgin without the stain of sin.

As a priest still serving at the altar and in public ministry at the monastery, all of these private thoughts swirled through my mind. It was a tension and conflict that I wrestled through in my prayer and through my study. My journal entries of the time reflect this inner conflict. This can be seen clearly in my entry on July 30, 2022, where I write:

There is a logical wholeness in Eastern Christianity. I can speak for hours and hours on and about Christian theology, the Church, and so on — completely sincere. Completely convincing — and convinced. Give sermons which people seem to love. All that in complete sincerity and honesty. And yet… and then… my deeper and inner thoughts. We move up and beyond that — like stepping through a painting and into another world — transcendent — full of mystery and color. That is Islam. My mind is here [in the Christian monastery] — in this thought-world. These duties. And then my heart is somewhere else. No contradiction, I feel. Just a deepening.

At this point, any good Christian would ask: “What about the Trinity? The Divinity of Christ? Surely there is some contradiction here?!”

It is true that there were some matters that I needed to work through, theologically. After all, Trinitarian Christianity had been deeply engrained in me day in and day out for nearly all of my life, and in a most radical way within the monastery. How could this change?

I think I shall pause here and save this for yet another installment. (An installment that I shall write out sooner than it has taken me to write this one, inshallah!)

Thank you for reading. And more importunately, thank you for your prayers, your duas, and your support.

I ask especially to keep all of our persecuted and martyred brothers and sisters of Palestine — both Muslim and Christian — in your prayers and duas. May God grant them strength, may He ease their pain and suffering, and may He wipe away every tear from their eyes.

May we also be found worthy to attain such a blessed state of spiritual martyrdom as a witness to the world and in light of the world to come. Inshallah.

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche (2016). The Antichrist, p.96.