The ‘Nomad Archetype’ and the ‘Great In-Between’: Part 1 — Deleuze and ‘A Thousand Plateaus’

This is a follow-up to my Part 1: Introduction.

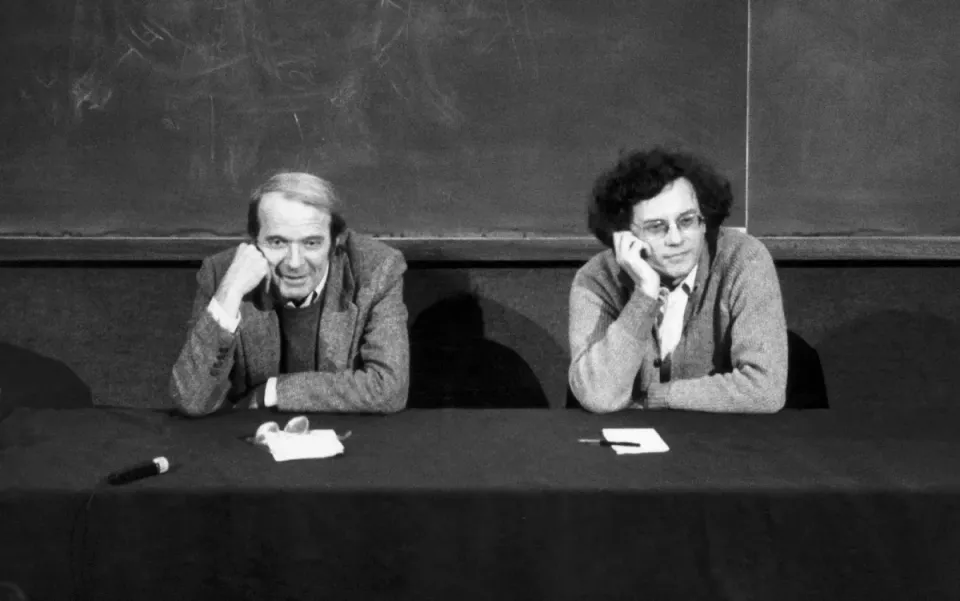

I suppose that the best place to start with my mini-series on the ‘Nomad Archetype’ and the ‘Great In-Between’ would naturally be the book that Gilles Deleuze co-authored with fellow French philosopher, Felix Guattari, entitled A Thousand Plateaus.

I had been meaning to read Deleuze for some time now, as he is up there as one of the ‘more important’ of our contemporary philosophers. His name often comes up in political circles and in discussion of current events. However, it wasn’t until my recent romanticized yearning for the Mongolian steppes that Deleuze really gained my attention. Somehow or other, the ‘Mongolian’ and ‘nomadic’ theme led me to Deleuze’s 1980 text which has been described as an experimental work of philosophy covering a wide range of subjects and topics including rhizomatic thought, psychoanalysis, art, culture, linguistics, history, philosophy, geography, politics, music, and so on. Each chapter of their 600+ page of work Deleuze calls a ‘plateau’ which can be read out-of-order and independently of the rest of the work. (Deleuze’s A Thousand Plateaus has been called the philosophical equivalent of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake — and Finnegans Wake being my favorite literary work, this immediately won me over.)

The Nomad Archetype and the concept of the Great In-between can be thought of as the philosophical and existential frameworks used by Deleuze to frame his thinking throughout A Thousand Plateaus. The Nomad in Deleuze’s thought is a symbol of freedom, fluidity, and non-conformity to rigid structures or territories. Rather than being defined by stable identities or fixed points (as “sedentary” people or societies often are), the nomad represents movement, multiplicity, and ‘becoming’. This archetype doesn’t settle in one place — literally or metaphorically — but instead exists in a continual process of change and what Deleuze calls ‘deterritorialization’. Nomadic life is not just about physical wandering but also about intellectual and spiritual wandering, always in search of new possibilities, new connections, and new territories of thought.

On ‘nomadism, and ‘deterritorialization’, Deleuze says:

“The nomad distributes himself in a smooth space; he occupies, inhabits, holds that space; that is his territorial principle. It is in this sense that the nomad is not primarily defined by movement. Rather, it is by the relation between the singularities of a nomad and the space they inhabit that nomadism exists.”

The nomad operates in smooth space — a fluid, non-linear, non-hierarchical realm that stands in contrast to the rigid structures of society. The nomad’s relationship to space is one of constant becoming, rather than belonging.

Of this ‘becoming’, Deleuze says:

“The life of the nomad is the intermezzo. Even the elements of his dwelling are conceived in terms of trajectories and are tied to the journey itself.”

This quote highlights the idea of the Great In-between — the nomad exists in an ‘interstitial’ space, an in-between that is more process than destination. The nomad’s life is defined by movement, flux, and the rejection of fixity.

As such, the sense of ‘freedom’ in the thought of Deleuze has a spatial and geographical aspect to it. The concept that emerges in his work which I call the Great In-Between refers to spaces or states that exist between defined categories, identities, or territories. For Deleuze, this in-between space (which he calls smooth space as opposed to striated space) is not fixed, ordered, or controlled. It is a space of flux, potential, and emergence — where boundaries dissolve, and new forms of life or thought can emerge. It is akin to the geographical space of the Mongolian steppes or the open desert, where space is marked more by action, relations, events, etc. in an open, directionless field. Smooth space is less about predefined structures (striated space) and more about the unfolding of events, affects, and encounters that refuse clear organization. Says Deleuze:

“A path is always between two points, but the in-between has taken on all the consistency and enjoys both autonomy and a direction of its own.”

The space between points or territories (rather than the points themselves) — that Great In-Between — becomes the primary focus. This is where the nomad’s power lies — in navigating the fluid, liminal spaces.

Thus we see Deleuze’s concept of nomadism as a rejection of fixity, focusing instead on movement, ‘becoming’, and inhabiting spaces of constant flux and transformation. The Great In-between is where creativity and new ways of thinking and living emerge. In this space, the ‘nomad’ thrives, constantly moving and adapting rather than being confined by binary oppositions (like settled vs. nomadic, center vs. periphery). It is a zone of experimentation and creativity, open to new ways of being and thinking.

And so, this new discovery of Deleuze was, for me, an explosive opening of thought and ‘revelation’, of sorts. It held up a mirror to my own way of thinking and my own modus operandi which had previously been unexplored in any real and conscious sense.

Deleuze’s concepts fit perfectly into my idea of the Nomadic Archetype as the archetype embodies the restless pursuit of new frontiers, both literal and conceptual. Similarly, the Great In-between is the fertile, unbounded space where new possibilities and ideas take root and flourish. Together, these ideas challenge fixed identities, linear progression, and stable categories, emphasizing flux, multiplicity, and becoming as central to human experience.

Of course, to some of my more traditionalist-minded readers, the thoughts of Deleuze may reek of a sort of post-modern ‘post-structuralism’ which Deleuze generally represents. But even here, I think Deleuze’s thoughts in A Thousand Plateaus defies such simple categorization. Upon reflection, I began to see parallels to what Deleuze was talking about in many various sources and traditions — religious, philosophical, or otherwise. In the thought of Ernst Jünger, who I’ve long considered my philosophical ‘hero’ and role-model of sorts. In the philosophy contained within the Tao Te Ching — a work which I used to carry around in my pocket through my teenage years. In various Islamic concepts of detachment from the dunya, or of this world. In the ‘process philosophy’ of Alfred North Whitehead. In Guénon and the Traditionalists. In political philosophy. In Thoreau. In Heraclitus. In anarchist thought. In ‘Bedouin Spirituality’. In the thought-world of Dune. And so on and so forth. All aspects that I will touch upon further in subsequent articles. But the concepts touched upon and expounded by Deleuze are at once both very contemporary/postmodern — and yet deeply traditional and, I would say, eternal.

It was Deleuze, finally, (for me) that opened up this door and thread all of these traditions, tendencies, and streams of thought together into one overarching picture and pattern.

Modern Nomad music

This is Part One of a series of (I hope) insightful and useful content. I do not wish to stray too far away from posting on matters of Islamic thought, Muslim life, and similar concerns, but I do feel that this is all inter-related in a very real sense. And I will continue in this line of thought, inshallah.

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language full-time with no income, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!