The ‘Nomad Archetype’ and the ‘Great In-Between’: Part 5 — Flannery O’Connor and ‘Dark Nomadism’

‘Southern-Gothic Nomadism’ and the ‘Christ-Haunted South’

“The body, lady, is like a house: it don’t go anywhere; but the spirit, lady, is like a automobile: always on the move, always…”

— Flannery O’Connor, ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’

In my previous installment in my series on ‘the nomadic archetype’ and the ‘Great In-Between’, I spoke about what I call the ‘nomadism of Dajjal’ and explained what my idea of ‘nomadism’ is not. The main idea of that article is that my concept of the ‘nomad archetype’ is not some sort of modern rootlessness disconnected from faith, family, home, place, tradition, etc. I wanted to counter this idea that my thoughts on ‘nomadism’ represent this sort of aimless, wandering rootlessness.

And yet… it is fair to say that this darker side of ‘nomadism’ can and does exist. I considered exploring this idea a bit further when I happened to come across a quote from one of my favorite writers — and a woman dear to my heart — Flannery O’Connor. And that is the quote at the beginning of this article:

“The body, lady, is like a house: it don’t go anywhere; but the spirit, lady, is like a automobile: always on the move, always…”

At first glance, one could be forgiven for thinking that this quote might mean something more ‘uplifting’ or ‘inspirational’. Superficially, it resonates with a type of modern, ‘free-spirit’ mindset. “Our bodies are heavy,” this modern mindset might say in interpretation, “but our spirits are FREE.”

However, this is not what Flannery O’Connor intended when she wrote this line for the character, Mr. Shiftlet, in her short story ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’. In the context of O’Connor’s work, this would be a wrong interpretation. Rather, this quote exemplifies the darker side of ‘nomadism’ as O’Connor saw it.

The Restless Nomad in Flannery O’Connor’s Writing

The above quote from “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” is indicative of Flannery O’Connor’s view of ‘nomadism’, both literal and spiritual/metaphorical, and it ties into her broader literary themes of faith, doubt, grace, etc. In much of O’Connor’s writing, her characters are often spiritually adrift or seeking something elusive — always just beyond the horizon, but never quite in reach. The idea of constant movement — of the spirit being like “an automobile, always on the move” — speaks to the wandering, restless, and unmoored nature of many of her characters.

‘Nomadism’ is traditionally associated with physical wandering, but in O’Connor’s stories, it frequently points to a deeper spiritual restlessness. Characters like Mr. Shiftlet (who spoke the above quote) are not only physically itinerant (he’s a drifter, after all), but also morally and spiritually unanchored. (Even the name “SHIFTlet” speaks to this reality.)

O’Connor’s American South, full of grotesque and flawed individuals, is a place where people are often in search of meaning or salvation but are unwilling to settle into the moral and spiritual “home” that might require humility or sacrifice.

In this context, the “house” is a symbol of stability, both moral and spiritual. It represents a fixed state, grounded in the present reality. The body, tied to the earth and human limitations, doesn’t go anywhere. It stays put. This echoes a lot of O’Connor’s Southern Catholic sensibilities, where grace and redemption are things that can be found in a fixed, rooted way — through the acceptance of one’s limitations and need for divine intervention.

However, the “spirit” being like an automobile — always in motion — represents a disconnection from that grounded reality. The constant motion of the automobile, the need to keep going, implies a restlessness that prevents Mr. Shiftlet and other similar O’Connor characters from finding peace or redemption. This ‘dark’ nomadic spirit avoids confrontation with deeper truths and commitments, particularly those involving faith, responsibility, and morality.

Flannery’s Characters as Nomadic Figures

“The world is almost rotten. That’s the truth… I can’t get away from the stink of this world.”

— Mr. Shiftlet in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own”

Mr. Shiftlet, Flannery’s character delivering the above metaphor of the soul as an automobile always on the move, embodies this sense of restlessness. He’s a drifter who refuses to settle down. Even when he fixes up an old woman’s car and marries her daughter, there’s no real commitment — he uses the situation to escape once again. His movement is physical but also represents a deeper kind of spiritual evasion, as he avoids confronting his own emptiness and moral corruption. He is always “on the move,” trying to outrun the weight of his responsibilities and the need to confront his spiritual state.

Mr. Shiftlet openly expresses his internal restlessness, constantly trying to escape what he perceives as the world’s corruption. Yet, his constant motion doesn’t lead to clarity or grace, but rather to further alienation and moral evasion.

The same can be said of the grandmother in what is arguably Flannery O’Connor’s greatest work, the short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find”.

The grandmother is also flighty and restless. She’s selfish and inconsiderate, and flits through life without taking much of anything seriously — not other people, and certainly not thoughts of responsibility, of real moral life, or of God.

In the end of the story, she is caught at gunpoint at the hands of “The Misfit” — a criminal on the run. I don’t want to give away the story for those who haven’t read it (and I highly encourage reading it!), but “The Misfit” delivers this line soon after their meeting:

“She would have been a good woman … if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

In speaking these words, The Misfit seems to say that people like the grandmother only confront truth or grace in extreme moments of most desperate need— when they are forced to stop their flighty carelessness and heedlessness. The grandmother’s superficial, moral drifting is cut short by her final moment of clarity — but it comes too late to save her.

In O’Connor’s wider body of work, we often see characters grappling with forms of existential and spiritual nomadism. Many of her protagonists are unsettled, resisting the grace that hovers near them, often in grotesque or dramatic ways. The nomadism in O’Connor’s characters often acts as a metaphor for the human condition, where people are in search of truth, but avoid the hard journey towards redemption. As O’Connor states in one of her private letters:

“All human nature vigorously resists grace because grace changes us and the change is painful.”

O’Connor here describes the root of spiritual restlessness. People resist grace because it forces them to confront uncomfortable truths, often preferring to remain in a state of wandering or avoidance. The “painful” change that grace brings can only come once this restless evasion ends.

A good example of this is the grandmother in “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Though a literal wanderer on a road trip, she only finds clarity about her own need for grace in the last moments of her life. Her physical journey mirrors her spiritual one, as both are marked by disorientation and a gradual, reluctant approach toward an uncomfortable truth. (Again… read the story! Or listen to it on YouTube.)

Nomadism and the Car as a Symbol

In many ways, the car in this quote could be seen as a symbol for modern mobility, representing freedom but also alienation. In O’Connor’s rural South, cars often signify a way to escape, a way to detach from family, tradition, or faith. The idea of perpetual motion — like nomads who have no fixed home — may seem liberating, but it also leads to rootlessness, preventing the characters from forming meaningful connections or achieving any form of grace.

Tension Between Rootedness and Movement

O’Connor’s work frequently contrasts a kind of restless nomadism with the possibility of rootedness — both physical and spiritual. Many of her characters are deeply flawed, yet there’s always the potential for them to receive grace. But in order to do so, they often need to stop running — whether that’s physically or spiritually. The spirit, like Mr. Shiftlet’s metaphorical automobile, must eventually stop moving, stop avoiding, and confront the reality of its condition.

In sum, this metaphor in the opening quote from “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” highlights a core tension in O’Connor’s work: the opposition between rootedness (the body, the house) and restless wandering (the spirit, the car). Nomadism in O’Connor’s characters often prevents them from confronting the deeper truths of their lives, keeping them from redemption or grace — something that requires them to stop, reflect, and accept their limitations.

‘Dark Nomadism’ and O’Connor’s ‘Christ-haunted South’

Flannery O’Connor’s famous observation that the South is “not Christ-centered but Christ-haunted” reflects her idea of nomadism within her work. The “Christ-haunted” South suggests a region where Christian belief and the presence of grace permeate the culture, but where people are often disconnected from the deep spiritual commitment and understanding that should accompany that presence. In this sense, the spiritual restlessness of O’Connor’s characters mirrors the broader condition of being haunted rather than centered — they are aware of something greater but cannot or will not fully grasp it.

The concept of being Christ-haunted, rather than Christ-centered, suggests that people are not fully anchored in their faith or moral convictions, even though they are surrounded by the symbols, language, and rituals of Christianity. This haunting presence implies a spiritual restlessness — people are aware of grace and redemption, but they drift away from it, either out of fear, resistance, or moral confusion.

As seen above, we see this in the characters of O’Connor’s stories. Many of her characters are spiritually “on the move,” avoiding the full implications of grace, much like the haunted South she describes. They sense the divine lurking behind their lives, but instead of embracing it, they wander aimlessly, never fully settling into the difficult, humbling work of faith. Their constant evasion and moral drifting are part of this larger haunting — they are perpetually pursued by grace, yet they resist it at every turn.

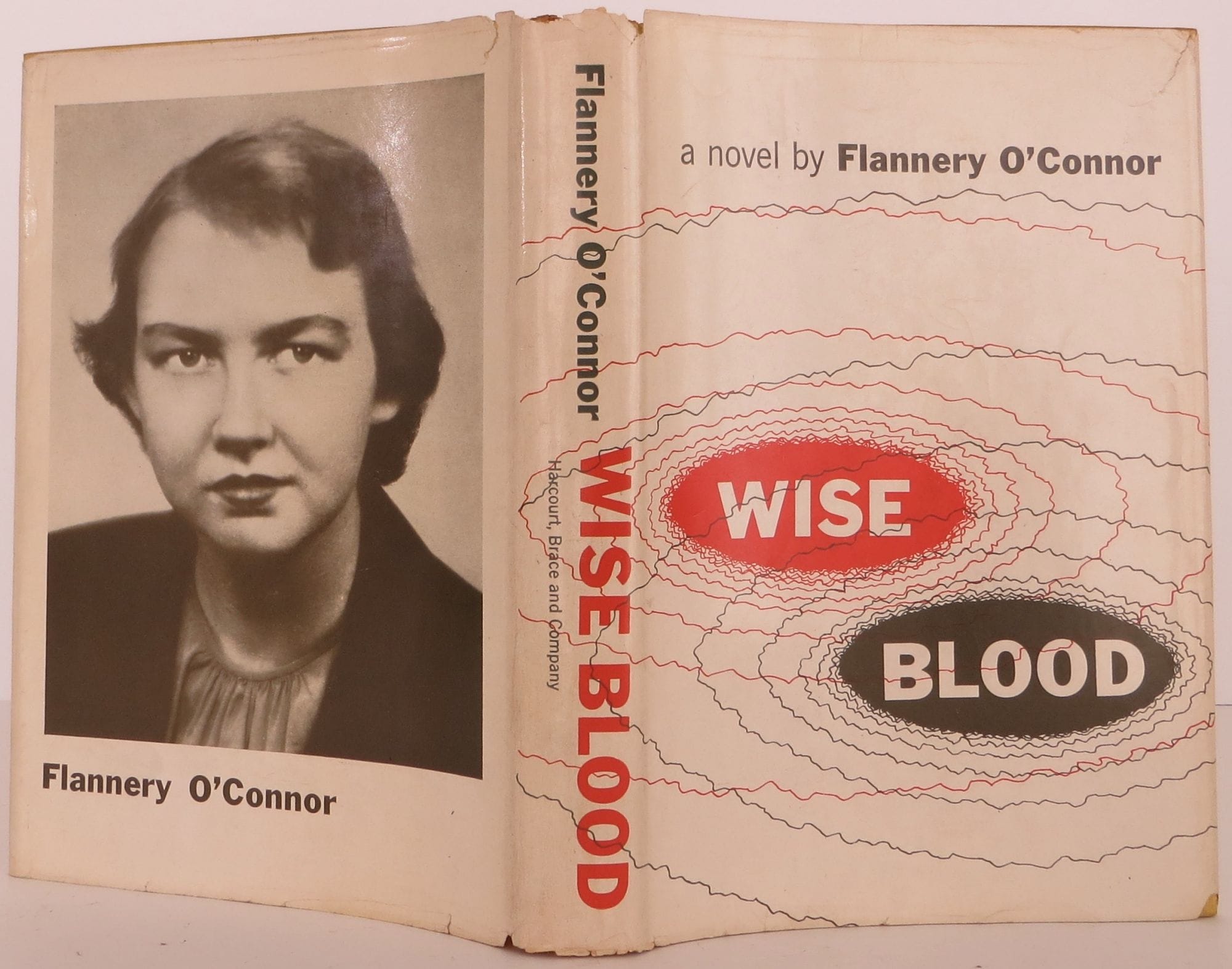

Nomadism in O’Connor’s Novel ‘Wise Blood’

In “Wise Blood,” Flannery O’Connor explores the idea of spiritual wandering and alienation through the character of Hazel Motes, whose restlessness reflects the “Christ-haunted” condition she described in the South. The novel is full of moments that highlight Motes’s struggle with faith, belief, and the presence of Christ — he is spiritually nomadic, rejecting yet haunted by religious truth.

Hazel Motes and His “Church Without Christ”

Hazel Motes, the protagonist, spends much of the novel actively rejecting Christianity, despite being haunted by its presence in his life. His establishment of a Church Without Christ is the ultimate expression of his spiritual wandering — he’s trying to run from the inescapable influence of grace.

“I want a church in which the blind don’t see and the lame don’t walk and what’s dead stays that way.”

This quote captures Motes’s rejection of the supernatural aspects of Christianity, but at the same time, it reflects his deep engagement with the faith he’s trying to escape. His Church Without Christ becomes a metaphor for his spiritual nomadism. He cannot shake the presence of Christ, so he creates a church defined by the absence of Christ, only to find that the absence is still a kind of haunting.

The Car in ‘Wiseblood’ (Once Again) as a Symbol of Nomadic Restlessness

Throughout the novel, as in the short story ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’, Hazel’s car is a key symbol of his restless movement and spiritual displacement. Motes drives his car almost obsessively, and his journey becomes a kind of aimless wandering — physically and spiritually. His constant movement echoes his inability to settle on a spiritual truth, as he tries to evade the haunting presence of grace in his life.

“Nobody with a good car needs to be justified.”

This quote encapsulates Hazel’s belief that material independence, symbolized by his car, can substitute for spiritual justification. He clings to the car as a way to avoid confronting the deeper, spiritual needs that reliance on God represents. His constant driving is emblematic of the nomadic evasion of grace — he’s trying to stay in motion to avoid being “caught” by it.

I could go on, but I think these examples suffice to show the larger themes and patters in O’Connor’s writing. In reality, this short article could be fleshed out to be a full-blown PhD thesis or stand-alone book in its own right. There is so much to say about Flannery O’Connor in this regard — and the more I reflect and research, the more I feel that I can and should say.

For our purposes here, however, I think this small taste is enough in order that we understand the bigger picture.

It was the serendipitous rediscovery of the opening quote a few days ago which lead me to this line of thought. While I intend to describe the ‘nomad archetype’ in a positive and constructive light in my series of articles — and even while I shot down some of the criticisms of this idea in my last article — I feel that it is fair to point to Flannery O’Connor as providing a real and serious critique of the ‘nomad’ idea from a darker viewpoint.

There is the understanding of ‘nomadism’ as I’ve explored in the works of Deleuze and within religious and spiritual contexts which can be rooted, positive, and dynamic. And yet, at the same time, there is a ‘nomadism’ which can represent a sort of unmoored restlessness, an aimless wandering, and loss of place and of spiritual grounding — some of which I have explored in my previous article, but which I feel is perfectly exemplified in the works of Flannery O’Conner.

To every good, there is an opposite and opposing corruption of the good. For example, one can use a knife to prepare a meal for a homeless person… or they could use the same knife for more sinister means. The intention and the aim is what is important. The inner state of a person is what matters.

Much of what O’Connor explores when she examines the darker aspects of ‘nomadism’ and of the ‘Christ-haunted South’ can be put under the category of what Carl Jung terms the ‘shadow self’. Jung’s concept of the shadow self refers to the unconscious and often hidden parts of our personality that we either ignore, repress, or deny because they don’t align with our conscious self-image. These traits are often negative or undesirable, such as anger, selfishness, or jealousy, but the shadow can also contain positive qualities that we’ve neglected, like creativity or ambition. In both cases, the ‘grotesques’ in Flannery O’Connor’s writings never fully realize either their good or bad qualities simply because they are constantly running away in an attempt to avoid a real confrontation with who they truly are. Thus, they avoid dealing with their sins and their darker aspects, while at the same time avoiding the salvific grace that is always available to them from a loving God.

In this series of articles on the “nomadic archetype” and what I call the “Great In-Between”, I feel that it is good to pause and to reflect on this critique of O’Connor, who is often so good at holding a mirror up to ourselves and showing us for who we are (or who we are capable of being) in her ‘grotesque’ characters — or at least the aspects of ourselves which we would most like to avoid. In what ways do we run from God? From grace? In what ways are we afraid to see the darker aspects of our own selves? In what ways are we capable of ‘fooling ourselves’ as too our true motivations and desires? (And for *bonus points*, how does this relate to the Biblical narrative of the Prophet Jonah?)

For these reasons — as well as for her profound religious and spiritual insight into the nature of human beings and of society — I have always adored Flannery O’Conner, who I refer to as my ‘Waffle House Dostoyevsky’. As such, I thought it fitting to give her a place here in my analysis as representing the ‘darker’ side of human nature and of our more problematic responses to Grace.

Jim White’s ‘Still Waters’ is a perfect encapsulation, in my opinion, of Flannery O’Connor’s ‘Christ-haunted South’. (And just as an aside note... my love for the American South and for Appalachia runs as deep as my love for Flannery O'Connor.)

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language full-time with no income, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!