The ‘Nomad Archetype’ and the ‘Great In-Between’: Part 7— Ernst Jünger and the ‘Anarch’

“Serapion the Sindonite traveled once on a pilgrimage to Rome. Here he was told of a celebrated recluse, a woman who lived always in one small room, never going out. Skeptical about her way of life — for he himself was a great wanderer — Serapion called on her and asked, ‘Why are you sitting here?’ To which she replied, ‘I am not sitting; I am on a journey.’”

Benedicta Ward, “The Desert of the Heart: Daily Readings with the Desert Fathers”, 42.

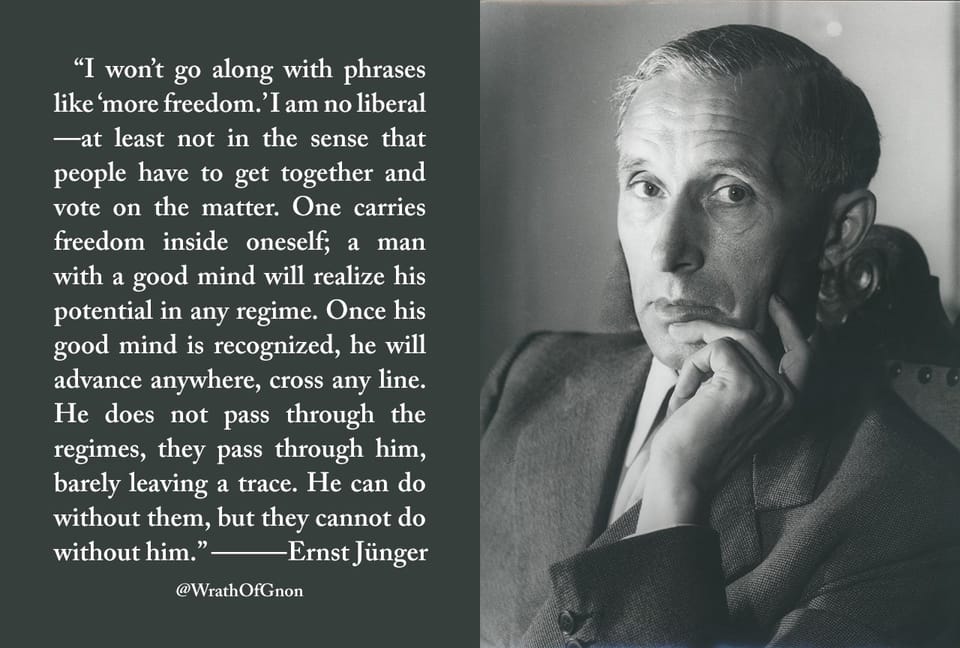

I have long stated that one of the ‘secular’ heroes of my life is Ernst Jünger — a man who penned one of the definitive accounts of the First World War (Storm of Steel) and who’s life spanned the whole arch of the 20th century. He was a man who saw the end of the Old Order of Europe, who saw the rise of Nazism in Germany, who was (as a German hero) reluctantly recruited into the SS, was involved in an assassination plot against Hitler, who became an influential intellectual in post-war Europe, was one of the first people who experienced LSD with its inventor, Albert Hofmann, in 1951, who enjoyed walks and studying insects around his rural Heidelberg home, and who finally died at the age of 102 after being received into the Roman Catholic Church just a year earlier.

Jünger was long a towering intellectual in Europe’s ‘Conservative Revolution’, yet has shown himself to be intellectually flexible in the face of changing times as situations through the progression of the 20th century.

His final major novel, Eumeswil (1977), was was perhaps his most important philosophical statement and a crystallization of his political beliefs.

In Eumeswil, Ernst Jünger presents the idea of the Anarch — a character who epitomizes absolute personal sovereignty. Unlike the anarchist, who is driven to disrupt external power structures, the Anarch remains inwardly autonomous, bypassing the need for conflict. As Jünger observes, “The special trait making me an anarch is that I live in a world which I ‘ultimately’ do not take seriously. This increases my freedom; I serve as a temporary volunteer.” The distinction between the ‘Anarchist’ and the ‘Anarch’ is key: the Anarch is an individual who has transcended the need for rebellion by achieving a profound and complete self-governance.

The Anarch, for Jünger, is very much ‘in the world, but not of the world’. He moves within society but remains unbound by it, inhabiting a state of inner freedom that allows him to observe and engage without attachment.

In a world that has become unmoored to enduring and eternal truths and values, the ‘Anarch’ retreats into a state of ‘inner exile’. Neither his action nor his inaction are dependent upon the state of matters within which he finds himself. Rather, ‘the Anarch’ becomes detached (as much as he can) from the corrupted world, and moves freely (internally) like the spiritual nomad in our archetypal understanding.

Deleuze’s Nomadism and Jünger’s Anarch: A Parallel Philosophy of Freedom

Gilles Deleuze’s concept of nomadism (which I’ve introduced in previous articles), echoes Jünger’s Anarch in important ways. For Deleuze, the nomad exists outside the constraints of traditional societal structures, not by opposing them directly but by operating on an entirely different plane. Nomadism is a form of “deterritorialization,” where the nomad navigates spaces without being defined by them. Deleuze writes, “The nomad has no history; he has only a geography.” This suggests a life lived in direct engagement with one’s environment yet outside the bounds of conventional social and historical constraints — a life that values movement, fluidity, and adaptability.

Similarly, the Anarch can be seen as a mental and spiritual nomad, navigating society while maintaining his independence. He does not resist by seeking to overthrow structures but instead resides in a “Great In-Between,” a realm beyond the reach of external control. According to Jünger, “the anarch has, as it were, no fixed abode, for he lives in his own world, which is perhaps why he feels so at home everywhere.” This liminal existence resonates with Deleuze’s notion of the “smooth space” of the nomad, where boundaries are fluid, and the individual remains unanchored by the fixed positions of identity, geography, or allegiance.

The Anarch and the Nomadic Archetype: Embracing the Great In-Between

The Anarch’s detachment from external structures reflects Deleuze’s “nomadic thought,” which values becoming over being. In Deleuzian terms, the Anarch embodies a line of flight — a movement away from prescribed forms of identity and authority, thus inhabiting what I have termed the “Great In-Between.” This space — neither fully inside nor outside society — is where the Anarch thrives. He is both observer and participant, free to move in and out of social roles without being fixed by them.

Where Deleuze’s nomad destabilizes traditional notions of space and belonging, Jünger’s Anarch destabilizes notions of authority and control. Just as the nomad’s movements are dictated not by territorial boundaries but by the rhythms of existence, the Anarch operates according to his own inner compass. Jünger’s Anarch, therefore, represents a way of being that aligns with Deleuze’s vision of life beyond rigid structures, a freedom born of detachment rather than opposition.

Sovereignty as a Path of Inner Freedom

The Anarch’s power is rooted in detachment — a quality essential to the Deleuzian nomad, who seeks freedom not through control over others but through self-determination and movement within open, undefined spaces. In Jünger’s words, “The anarch sees events as part of an eternal process; he is a contemporary of all ages.” This temporal detachment enhances the Anarch’s freedom, allowing him to view history not as a linear narrative but as a vast, interconnected web. Here again, we see the resonance with Deleuze’s nomad, who perceives reality as fluid and interconnected rather than rigid and hierarchical.

The Anarch’s ability to remain both within and outside society recalls the nomadic archetype’s timeless wandering. Both the Anarch and the nomad are inhabitants of the Great In-Between, embracing a realm where they engage with the world while maintaining their autonomy. This way of life, defined by adaptability, resilience, and mental flexibility, allows the Anarch to exercise a quiet but potent sovereignty that remains untouched by societal shifts.

The Anarch and the Nomad: Models for a New Sovereignty

In a contemporary context where fixed roles and identities often feel restrictive, Jünger’s Anarch and Deleuze’s nomad offer models of freedom that transcend these boundaries. By cultivating an inner sovereignty, they achieve a self-directed autonomy that does not rely on outward worldly validation. As Jünger writes, “Every anarch is a monarch of his own kingdom, that is, of his self.” This internal kingdom represents the highest form of freedom, one that resonates with the nomadic ethos of independence and self-reliance.

In embracing these archetypes, one can navigate the “Great In-Between” with the confidence of the nomad and the insight of the Anarch, fostering a life defined by adaptability and inner authority. Whether through the lens of Jünger’s Anarch or Deleuze’s nomad, these figures remind us that true freedom is found not in external circumstances but in the profound act of self-sovereignty and self-mastery.

People of Faith will resonate with this. For truly, this world is not our home. We must “be in the world, but not of it.” While what happens in this world certainly matters, we are ultimately not attached to it. Our true freedom, therefore, doesn’t rely on the circumstances of the world in which we find ourselves. Our true freedom is an internal freedom — regardless of whatever external outcome and circumstances we may encounter. Because at the end of the day, God is the ultimate reality… and in the final moment, it is just myself and God. Everything aligns according to that understanding.

And so that is why we can be ascetical solitaries in a cave going on a ‘great journey’, while also — at the same time — we can be living ‘in the world’ and be ‘great solitaries’, in the spiritual sense.

Christians and Muslims (two communities which I know very well) have traditionally treaded this path of being ‘in the world but not of it’ according to their perspective faiths. A Christian/Muslim lives and works in the midst of society, yet he (or she) is not fundamentally apart from society. There is a detachment from the ways of the world, and a total commitment to God — to Allah. Yet this is a theme of non-attachment found in almost all traditional understandings of the world.

Conclusion

In synthesizing Ernst Jünger’s Anarch and Gilles Deleuze’s nomad, we encounter two figures who epitomize a sovereignty that operates beyond traditional boundaries — one rooted in inner autonomy, the other in movement and adaptability. Both the Anarch and the nomad embrace a realm of detachment, a “Great In-Between,” where freedom is maintained not through opposition but through a refusal to be bound by external structures or identities. For the Anarch, sovereignty is an inner monarchy; for the nomad, it is a fluid engagement with open spaces. Together, these archetypes illuminate a path of self-reliance and inner authority, suggesting that true freedom in the modern world comes from cultivating a resilient independence that is both mental and spiritual.

In this way, they invite us to consider a form of autonomy that transcends place and position, advocating a way of being that is at once engaged with the world and untethered by it.

To quote Surah Al-Hadid (57:20):

“Know that the life of this world is only play and amusement, pomp and mutual boasting among you, and rivalry in respect of wealth and children... And what is the life of this world, except the enjoyment of delusion.”

And as the the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) said,

"Be in this world as though you were a stranger or a traveler along a path" (Sahih Bukhari).

This hadith suggests that a person should approach life in the world as temporary, preparing for the ultimate destination in the ‘next world’ rather than becoming overly attached.

Both the Quran and Hadith encourage Muslims to fulfill their responsibilities in this world while staying mindful that it is a temporary state, always keeping the the ‘next word’ in view. This detachment aligns well with the notion of being "in the world, but not of it."

Thus, we find in both the Christian and the Islamic understanding a sort of ‘nomadism’ which is found in Jünger’s concept of the Anarch.

This world is not our ultimate home. Our true freedom is found in an attachment elsewhere.

For an authoritative collection of Eumeswil quotes, see here.

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language full-time with no income, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!