Tradition Beyond Left and Right: Islam, Conservatism, and the Limits of Liberalism (An Addendum)

American political “conservatism” right now is much discussing the tragic demise (and newly canonized sainthood) of Charlie Kirk after his horrific public assassination a few days ago. But today, my thoughts have been drawn to a very different American conservative ‘Kirk’ — an often forgotten “saint” of 20th century American conservative thought — the phenomenal self-described “Bohemian Tory” that was Russell Kirk.

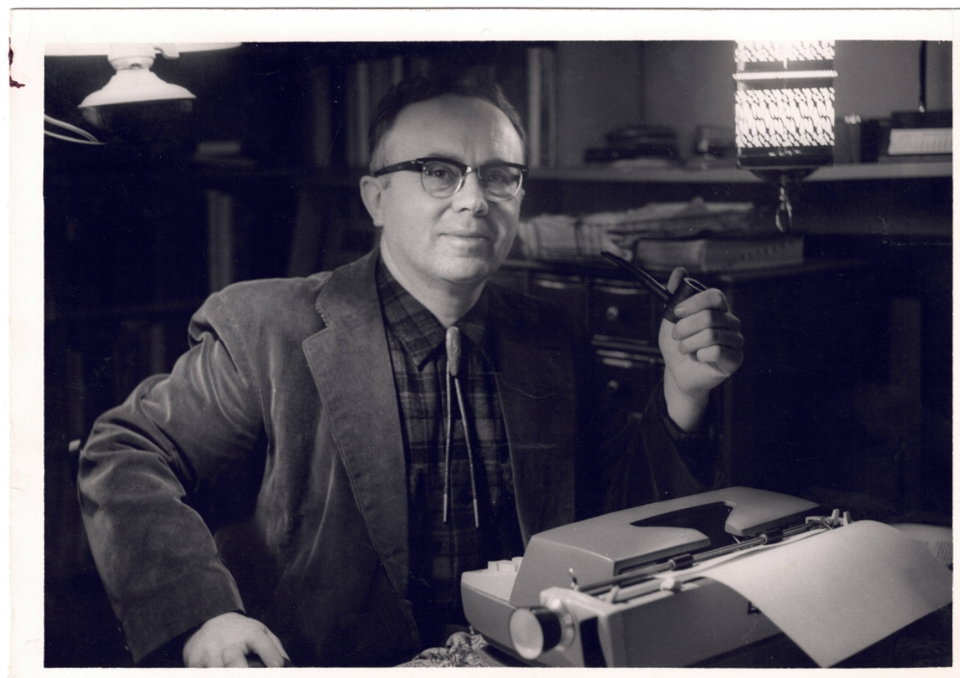

Russell Kirk (1918–1994) stands as one of the hallowed figures of 20th-century American conservative thought. Best known for his landmark work The Conservative Mind (1953), he almost single-handedly gave intellectual coherence to post-war conservatism, rooting it not in party politics but in a broader philosophy of order, tradition, and moral imagination. Alongside figures like William F. Buckley Jr. and Richard Weaver, Kirk helped establish a conservative intellectual tradition that sought to preserve what T. S. Eliot once called “the permanent things” — the enduring truths of faith, community, and inherited wisdom — against the corrosions of modern liberalism and ideology.

It was a Facebook post by a fellow Muslim that brought me to thinking of Russell Kirk once again. It was a post that led me to re-frame my previous political explanation within the context of what Russell Kirk saw as the key principles of American conservatism. Here is the Facebook post in full:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗻𝗲𝗲𝗱 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗹𝗶𝗺 𝗔𝗺𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗰𝗮𝗻𝘀 𝘁𝗼 𝘂𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗿𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝘂𝘀𝘂𝗹 (𝗳𝗼𝘂𝗻𝗱𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝗮𝗹 𝗽𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗽𝗹𝗲𝘀) 𝗼𝗳 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗹𝗶𝗯𝗲𝗿𝗮𝗹 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘀𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗲 𝗽𝗮𝗿𝗮𝗱𝗶𝗴𝗺𝘀:

When discussing binaries such as left / right or liberal / conservative, it is important to understand that these categories serve more as ideological vestiges, and less as concrete traditions. In reality, what are often described as two competing factions are, in fact, two facets of the same liberal paradigm — progressive liberalism and classical liberalism.

For nationalist conservatives such as Yoram Hazony, the authentic American conservative tradition ended in the mid-century. For the postliberal Patrick Deneen, the American conservative tradition ended at the founding of the country — which immediately adopted a uniquely liberal foundation, much to the chagrin of the anti-federalists.

Both, however, envision the authentic conservative paradigm as being wholly illiberal. And while modern conservatives — Reagan-era fusionists, neocon war hawks, free market capitalists, libertarians — may wear the hat of American conservatism, it is their indebtedness to liberalism that renders their claim purely nominal.

Though both conservatism and liberalism stem from specific traditions — conservatives seeing their paradigm as an extension of the Abrahamic message, and liberals envisioning their rationalist endeavor as the product of universal reason — it is important for us, in particular Muslim Americans, to understand the foundational principles of both paradigms to truly assess our overlap and points of divergence.

Contrary to the popular conception of the American conservative as being defined by the limitations they seek to place on centralized government, the foundational principles that undergird the conservative paradigm — as outlined by political theorist Russel Kirk — consist of:

1. A belief in a God-given, transcendent enduring moral order.

2. An adherence and deference to tradition, custom and continuity.

3. The family — and not the individual — as the foundational building block of society; which then, ideally, work together to form healthy localized communities, and thus healthy nations.

4. A conviction that civilized society requires hierarchy — orders and classes — as opposed to the utopian “classless society.”

5. An acknowledgement that no perfect social order can ever be created — only attempts at justice moderated by the contending forces of progress and prudence.

Whereas the foundational principles of the liberal paradigm — as informed by Lockean Enlightenment liberalism — can be understood as follows:

1. All human beings are perfectly free and equal by nature.

2. Civic obligations arise from the consent of the individual.

3. Government exists due to the consent of a large number of individuals, and its only legitimate purpose is to enable these individuals to make use of their natural freedoms.

4. These premises are universally valid truths, which every individual can rationally derive on their own, if they choose to do so.

In consideration of the maxim: lā mushāḥḥah fī al-iṣṭilāḥ (“There is no argumentation over terminology”), it is critical to outline what we mean when we use loaded words such as liberal or conservative, so as to not disparage foundational principles that we do, indeed, hold to be valid.

When Muslims make claims such as “Islām is neither liberal nor conservative” — though the intent is surely to say “Islām is neither Democratic nor Republican,” which is undoubtably true — the original statement undermines the reality that, as practicing religious people, we are by definition conservative.

Our religious framework as Ahl al-Sunnah wa’l-Jamāʿa (People of Prophetic Tradition and Community) dictates that our deference to the Abrahamic path — including its conception of practice, ritual, community, family, human rights — is by definition a conservative endeavor, though conservative in its most authentic form.

This becomes particularly pertinent when we map our contemporary political alliances, as exemplified in the reaction that followed the publication of the 2023 open letter, Navigating Differences. In what appeared to be a cut-and-dry exposition of Islām’s normative views on sexual orientation, a significant portion of both Muslims and non-Muslims interpreted the message as an extension of Christian White Nationalist discourse or as capitulating to the alt-right propaganda machine. Of course, hysteria ensued.

This sort of distortion only occurs when we maintain convenient ambivalence about what it is we actually believe — and as someone who spent a large majority of their adult life as a self-described progressive non-Muslim — I can assure you your allies, the ones who defend you against the vitriolic rhetoric of the right, do so because they think you’re “one of the good ones.”

As an aside, my thoughts on Russell Kirk always bring me back to a moment in 2008 in which I was sitting at a local Starbucks reading Kirk’s The Conservative Mind, when a Roman Catholic seminary friend (who I often saw at the coffee shop) sat down to talk to me as he usually did. When he saw I was reading Russell Kirk, his general friendly demeanor turned into one of revulsion. “Why would you want to read him?” he asked. At that moment, our friendship seemed to change, and I was no longer “one of the good ones”. I was always puzzled and slightly amused at that response. But I realize now that reading Kirk was a sin against the liberal order — even (and perhaps especially) for a Roman Catholic seminarian.

But I can explain.

In my last essay, I described my political stance as that of a traditionalist anti-liberal Leftist. To some, that phrase sounds contradictory. How can one be both rooted in tradition and opposed to liberalism, yet still stand on the Left? Isn’t tradition the natural ground of the Right, and revolution the terrain of the Left? But the more I reflect, the more I see my position as bearing deep resonance with Russell Kirk’s vision of conservatism — though Islam, and the politics that flow from it, both extend and transform that particular vision.

Kirk, often called the father of American post-war conservatism, insisted that conservatism was not reducible to partisan politics. “Conservatism is not a political system,” he wrote, “but a way of looking at the civil social order.” That way of looking began from the conviction that there is an enduring moral order, transcendent and binding, without which liberty collapses into license, and democratic politics into mob rule. Islam, in this regard, is far more radical in its affirmation than most Western conservatives. Tawḥīd — the oneness of God — is precisely the recognition that moral order is not constructed but revealed. The Qur’an calls itself “guidance for those conscious of God” (2:2), grounding all social and political life in divine truth. In this sense, both Kirk and Islam speak with one voice: freedom is only real when it is tethered to virtue.

Yet Kirk’s conservatism was not merely about order; it was also about continuity. He believed societies thrive when they preserve inherited customs and conventions, those fragile vessels of wisdom accumulated across generations. Islam, too, is a faith of continuity — the chain of transmission (isnād) binding one generation of believers to another, the prayers said today in Pittsburgh echoing those said in Medina fourteen centuries ago. At the same time, Islam is not antiquarian. It critiques traditions that entrench injustice. The Qur’an warns: “When it is said to them, ‘Follow what God has revealed,’ they say, ‘No, we will follow what we found our forefathers upon.’ Even though their forefathers understood nothing?” (2:170). Where Kirk sometimes leaned toward preservation for its own sake, Islam insists that continuity must be measured against revelation and justice. This is where my anti-liberal Leftism enters: tradition is precious, but it is not an idol. It must serve the dignity of man, or it betrays its purpose.

Kirk was also a thinker of prudence, warning that change must be weighed in light of long-term consequences because humanity is deeply flawed. “Any public measure ought to be judged by its probable long-run consequences,” he wrote. Islam shares this realism. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said, “Deliberation is from God; haste is from Satan.” And the Qur’an acknowledges our frailty: “Indeed, man is ever unjust and ignorant” (33:72). But Islam also refuses to allow prudence to calcify into timidity. There are times when justice demands confrontation, not compromise. Ali ibn Abi Talib captured this tension well: “Silence in the face of injustice is a mute devil.” Kirk feared revolution; Islam preserves space for it, so long as it is in obedience to God and against Pharaohs who oppress. My position follows this prophetic line — realism about human limits, but refusal to sanctify systems that thrive on oppression.

Kirk also praised social variety. He thought a healthy society must honor differences — between classes, callings, and associations — rather than collapse everything into uniformity. Here again Islam speaks in harmony: “Among His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the diversity of your languages and your colors” (30:22). But where Kirk could drift into romanticizing hierarchy, Islam insists on equality before God. The Prophet ﷺ, in his final sermon, declared: “No Arab has superiority over a non-Arab, nor a non-Arab over an Arab; no white over a black, nor a black over a white — except in piety.” Variety is divine, but exploitation is not. This is also why my Leftism remains integral: difference is to be celebrated, but inequality must be opposed.

It is on economics, however, that the divergence grows starker. For Kirk, private property is the cornerstone of freedom. Without it, he believed, individuals would be at the mercy of the state. Islam, too, affirms property rights — but only as a trust from God. Wealth is bounded by obligation. The Qur’an is blunt: “In their wealth is a right for the beggar and the deprived” (51:19). Hoarding, speculation, and usury are condemned. Here is the break with both Kirkian conservatism and liberal capitalism: Islam insists that property must serve justice. And this, again, is where my traditionalist anti-liberal Leftism stands with it. As José Carlos Mariátegui wrote of socialism in Latin America, it must be “a heroic creation” rooted in the traditions of the people, not an imitation of foreign ideologies. Property, too, must be rooted in moral purpose, not mere accumulation.

Still, Kirk’s final insight — that society must balance permanence with change — finds perhaps its clearest expression in Islam itself. Revelation is eternal, yet interpretation (ijtihād) adapts it to new contexts. Permanence and flexibility, form and renewal: this balance is precisely what liberalism cannot hold, because liberalism uproots all bonds in the name of “progress,” leaving individuals naked before market and state. My own politics is anti-liberal because it refuses this uprooting; it is traditionalist because it insists on the sacred as the axis of life; it is Leftist because it demands justice for the poor and solidarity with the oppressed.

In truth, Islam does not fit neatly within these modern American political categories of “Left vs. Right”, but we can still lay out a grounds within it upon which we stand.

What, then, do we conserve, and for whom? Kirk wanted to conserve Western civilization, and in doing so he often made peace with capitalism. Islam — and the politics I claim — is more universal. It seeks to conserve the moral order revealed by God, to preserve the ties of community, and to defend those most crushed by systems of exploitation. If Kirk reminds us of what must be conserved, Islam reminds us of who must be defended. And between those two lies a politics that is neither Right nor Left in the American sense, but both more ancient and more radical: rooted in God, in justice, and in human dignity.

This vision is a far cry from what passes for “Christian” politics in America today. On the right, we see an embittered nationalism cloaked in biblical language but hollow of mercy, solidarity, or humility. It waves the cross while despising the stranger, cheers bombing campaigns of schools, hospitals, refugee camps and churches while chanting about “family values,” and it treats Christianity as a tribal badge in the culture war. Jesus warned against such hypocrisy: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within are full of dead people’s bones and all uncleanness” (Matthew 23:27). This is the “Christian” Right of our time: polished, loud, powerful, but inwardly corrupt. And it is not hard to imagine Christ’s words to them echoing from the Gospel of Matthew: “Many will say to me on that day, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and in your name drive out demons, and in your name perform many miracles?’ Then I will tell them plainly, ‘I never knew you. Depart from me, you workers of lawlessness’” (Matthew 7:22–23).

Yet if the Right has hollowed out Christianity into idolatry of nation and tribe, the liberal establishment has its own false religion. “Wokeness” has become a kind of secular orthodoxy and moralism where identities are weaponized into endless grievance, hashtags stand in for solidarity, and the sacred is flattened into slogans. It dismisses tradition as bigotry, faith as superstition, and community bonds as oppression. In the end, it offers not liberation but exhaustion — a marketplace of outrage in which every cause is consumed and discarded like yesterday’s brand label. It is an endless revolution with no ultimate resolution.

Against both, I would set what I have called a traditionalist anti-liberal Leftism: rooted in the sacred, critical of exploitation, and unwilling to bend either to the tribal cruelty of the right or the rootless cosmopolitan relativism of the left. It is a politics that insists, with the Qur’an, “Stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to God, even if against yourselves or your parents or your kin” (4:135). That means no blind loyalty to the “red team” or the “blue team.” It means conserving what is holy, rejecting what is corrupt, and building communities where justice is not a slogan but a way of life. It means ending the exploitation of both Islam and Christianity as secular tools towards a secular, party politics and and towards a true transformation of society.

Islam offers not another ideology but a reminder: that God is One, that life is sacred, that wealth is a trust, and that community is a mercy. The Qur’an commands: “Indeed, God enjoins justice, excellence, and giving to relatives, and forbids immorality, wrongdoing, and transgression” (16:90). This is not private advice but a public charge. And it is a charge that any person of faith — no matter what their creed — can understand and accept.

As the Sufi master Junayd of Baghdad said: “The water takes on the color of its cup.” If our hearts are corrupted, so too will be our politics; if our hearts are illumined, then justice can flow outward into society.

The call, then, is simple: refuse the false and violently divisive binaries of this age, conserve what is holy, stand with the oppressed, and build a life where justice is more than a slogan within identity politics — both “Left” and “Right”.

Submit to God, guard your humanity, and do not sell your soul for the lies of the age — for truth endures, even when empires of this world fall, as they all inevitably do. For the Day will come when every falsehood perishes and only truth remains. And I think many of us will be surprised where we stand when that day inevitably comes.

UPDATE:

A word from Shaykh Yusuf bin Sadiq al Hanbali — a man whom I greatly admire. (I just came across this not too long after writing this article.)

I feel that it is generally along the lines of what I said above. (If I am mistaken in anything, please forgive me.)

If you like this content, please consider a small donation via PayPal or Venmo. I am currently studying Islam and the Arabic language, and any donation — however small! — will greatly help me to continue my studies, my work, and my sustenance. Please feel free to reach me at saidheagy@gmail.com.

Thank you, and may God reward you! Glory to God for all things!